Articles

- Page Path

- HOME > Restor Dent Endod > Volume 40(3); 2015 > Article

- Open Lecture on Statistics Statistical notes for clinical researchers: Type I and type II errors in statistical decision

- Hae-Young Kim

-

2015;40(3):-252.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.5395/rde.2015.40.3.249

Published online: June 30, 2015

Department of Health Policy and Management, College of Health Science, and Department of Public Health Sciences, Graduate School, Korea University, Seoul, Korea.

- Correspondence to Hae-Young Kim, DDS, PhD. Associate Professor, Department of Health Policy and Management, College of Health Science, and Department of Public Health Sciences, Graduate School, Korea University, 145 Anam-ro, Seongbukgu, Seoul, Korea 136-701. TEL, +82-2-3290-5667; FAX, +82-2-940-2879; kimhaey@korea.ac.kr

©Copyrights 2015. The Korean Academy of Conservative Dentistry.

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/) which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

- 4,717 Views

- 66 Download

- 37 Crossref

Tables & Figures

REFERENCES

Citations

Citations to this article as recorded by

- Sampling Methods and Sample Size Determination in Clinical Research: An Educational Review

Azzam Zrineh, Maysa Al‐Usta, Abdallah Alwawi

Journal of General and Family Medicine.2026;[Epub] CrossRef - Aquatic Compared With Land‐Based Exercises on Gross Motor Function of Children/Adolescents With Cerebral Palsy: A Systematic Review With Meta‐Analysis

Elton Pauluka, Luize Souto Ceolin, Laís Coan Fontanela, Adriana Neves dos Santos

Child: Care, Health and Development.2025;[Epub] CrossRef - The basic statistical concepts and their interrelationships in diagnostic research

Yitao Mao, Juxiong Xiao, Liping Zhu, Yu Zhang, Yueshuang Leng, Qingling Li, Ying Li, Chuyi Liu, Luqing Zhao

Postgraduate Medical Journal.2025; 101(1193): 263. CrossRef - Basic Statistics for Radiologists: Part 1—Basic Data Interpretation and Inferential Statistics

Adarsh Anil Kumar, Jineesh Valakkada, Anoop Ayyappan, Santhosh Kannath

Indian Journal of Radiology and Imaging.2025; 35(S 01): S58. CrossRef - Quantitative Methodology for Assessing the Quality of Direct Laser Processing of 316L Steel Powder Using Type I and Type II Control Errors

Oleksandr Vasilevskyi, Alexandra Woods, Matthew Jones, Michael Cullinan

Electronics.2025; 14(7): 1476. CrossRef - Platelet Rich Products in Cleft Palate Repair

Samer T. Elsamna, Fayssal Alqudrah, Mahnoor Khan, Teagen Smith, Jon Robitschek, Julia Toman

The Cleft Palate Craniofacial Journal.2025;[Epub] CrossRef - On the effect of flexible adjustment of the p value significance threshold on the reproducibility of randomized clinical trials

Farrokh Habibzadeh, Christine E. King

PLOS One.2025; 20(6): e0325920. CrossRef - Replication, robustness and the angst of false positives: a timely target article and its multifaceted comments

Dan Dediu, Maria Koptjevskaja-Tamm, Kaius Sinnemäki

Linguistic Typology.2025; 29(3): 459. CrossRef - Association between estimated intelligence quotient and treatment outcome in young patients with posttraumatic stress disorder treated with developmentally adapted cognitive processing therapy

Regina Steil, Judith Weiss, Babette Renneberg, Rita Rosner

Cognitive Behaviour Therapy.2025; : 1. CrossRef - Association of climate awareness with urban mobility and consumption behaviour in Accra: a path analysis

Nestor Asiamah, Theophilus Kofi Anyanful, Musah Osumanu Doumbia, Nana Benyi Ansah, Frank Frimpong Opuni, Isaac Aidoo, Faith Muhonja, Simon Mawulorm Agyemang, Cosmos Yarfi, Prince Koranteng Kumi, Kafui Agormeda-Tetteh, Toku Lomatey, Eric Eku

Transportation.2025;[Epub] CrossRef - A quantitative and qualitative assessment of differential privacy’s ability to support collaborative research using a real-world data analysis

David P Gieser, Ashna R Arya, Rebecca Lee Smith, John A Vozenilek, Vishwanath Raman, Jonathan A Handler

JAMIA Open.2025;[Epub] CrossRef - Case study: U.S. airline performance and delay analysis using SAS

Shwadhin Sharma

Journal of Information Technology Teaching Cases.2025;[Epub] CrossRef - Reinterpretation of the results of randomized clinical trials

Farrokh Habibzadeh, Teerapon Dhippayom

PLOS ONE.2024; 19(6): e0305575. CrossRef - Design and validation of a diagnostic suspicion checklist to differentiate epileptic from psychogenic nonepileptic seizures (PNES-DSC)

Pau Sobregrau, Eva Baillès, Joaquim Radua, Mar Carreño, Antonio Donaire, Xavier Setoain, Núria Bargalló, Jordi Rumià, María V. Sánchez Vives, Luis Pintor

Journal of Psychosomatic Research.2024; 180: 111656. CrossRef - CPV Monitoring - Optimization of Control Chart Design by Reducing the False Alarm Rate and Nuisance Signal

Naveenganesh Muralidharan, Thatsinee Johnson, Leyla Rose, Mark Davis

Science Journal of Applied Mathematics and Statistics.2024; 12(2): 20. CrossRef - Risk Factors and Dynamic Nomogram Development for Surgical Site Infection Following Open Wedge High Tibial Osteotomy for Varus Knee Osteoarthritis: A Retrospective Cohort Study

Haichuan Guo, Bixuan Song, Ruijuan Zhou, Jiahao Yu, Pengzhao Chen, Bin Yang, Naihao Pan, Chengsi Li, Yanbin Zhu, Juan Wang

Clinical Interventions in Aging.2023; Volume 18: 2141. CrossRef - Psychiatric and psychological assessment of Spanish patients with drug-resistant epilepsy and psychogenic nonepileptic seizures (PNES) with no response to previous treatments

Pau Sobregrau, Eva Baillès, Mar Carreño, Antonio Donaire, Teresa Boget, Xavier Setoain, Núria Bargalló, Jordi Rumià, María V Sánchez Vives, Luís Pintor

Epilepsy & Behavior.2023; 145: 109329. CrossRef - Cold Water Immersion Directly and Mediated by Alleviated Pain to Promote Quality of Life in Indonesian with Gout Arthritis: A Community-based Randomized Controlled Trial

Maria Dyah Kurniasari, Karen A. Monsen, Shuen Fu Weng, Chyn Yng Yang, Hsiu Ting Tsai

Biological Research For Nursing.2022; 24(2): 245. CrossRef - The impact of COVID-19 infection on hip fracture 30-day mortality

Ahmed Fadulelmola, Rob Gregory, Gavin Gordon, Fiona Smith, Andrew Jennings

Trauma.2022; 24(2): 109. CrossRef - Adjuvant radiation vs Chemoradiation in HPV+ oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma with extranodal extension

Samer T. Elsamna, Ghayoour S. Mir, Ibraheem Shaikh, Rohan Shah, Soly Baredes, Richard Chan Woo Park, Dylan F. Roden

Oral Oncology Reports.2022; 1-2: 100003. CrossRef - Improving Student Attitudes and Academic Performance in Introductory Biology Using a Project-Based Learning Community

Tyesha N. Burks

Journal of Microbiology & Biology Education.2022;[Epub] CrossRef - Algorithm for sample availability prediction in a hospital-based epidemiological study spreadsheet-based sample availability calculator

Amrit Sudershan, Kanak Mahajan, Rakesh K. Panjaliya, Manoj K. Dhar, Parvinder Kumar

Scientific Reports.2022;[Epub] CrossRef - Psychiatric and Psychosocial Characteristics of a Cohort of Spanish Individuals Attending Genetic Counseling Due to Risk for Genetically Conditioned Dementia

Pau Sobregrau, Josep M. Peri, Raquel Sánchez del Valle, Jose L. Molinuevo, Bernardo Barra, Luís Pintor

Journal of Alzheimer's Disease Reports.2022; 6(1): 461. CrossRef - Interactions in the 2×2×2 factorial randomised clinical STEPCARE trial and the potential effects on conclusions: a protocol for a simulation study

Markus Harboe Olsen, Aksel Karl Georg Jensen, Josef Dankiewicz, Markus B. Skrifvars, Matti Reinikainen, Marjaana Tiainen, Manoj Saxena, Anders Aneman, Christian Gluud, Susann Ullén, Niklas Nielsen, Janus Christian Jakobsen

Trials.2022;[Epub] CrossRef - Test Corrections Appear To Benefit Lower-Achieving Students in an Introduction to Biology Major Course: Results of a Single-Site, One-Semester Study

Kyeorda Kemp

Journal of Microbiology & Biology Education.2021;[Epub] CrossRef - The impact of COVID-19 infection on hip fractures 30-day mortality

Ahmed Fadulelmola, Rob Gregory, Gavin Gordon, Fiona Smith, Andrew Jennings

Trauma.2021; 23(4): 295. CrossRef - The effectiveness of the role of advanced nurse practitioners compared to physician-led or usual care: A systematic review

Maung Htay, Dean Whitehead

International Journal of Nursing Studies Advances.2021; 3: 100034. CrossRef - p-Hacking as a Questionable Research Practice in Industrial and Organizational Psychology

Bogdan Cocoș

Studia Doctoralia.2021; 12(1): 1. CrossRef - Gene–environment interaction: Oxytocin receptor (OXTR) polymorphisms and parenting style as potential predictors for depressive symptoms

Rebecka Keijser, Cecilia Åslund, Kent W. Nilsson, Susanne Olofsdotter

Psychiatry Research.2021; 303: 114057. CrossRef - Heart Failure Development in Obesity: Underlying Risk Factors and Mechanistic Pathways

Shabbar Jamaly, Lena Carlsson, Markku Peltonen, Johanna C. Andersson-Assarsson, Kristjan Karason

ESC Heart Failure.2021; 8(1): 356. CrossRef - Mapping social reward and punishment processing in the human brain: A voxel-based meta-analysis of neuroimaging findings using the social incentive delay task

D. Martins, L. Rademacher, A.S. Gabay, R. Taylor, J.A. Richey, D.V. Smith, K.S. Goerlich, L. Nawijn, H.R. Cremers, R. Wilson, S. Bhattacharyya, Y. Paloyelis

Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews.2021; 122: 1. CrossRef - Experts’ perceptions on the use of visual analytics for complex mental healthcare planning: an exploratory study

Erin I. Walsh, Younjin Chung, Nicolas Cherbuin, Luis Salvador-Carulla

BMC Medical Research Methodology.2020;[Epub] CrossRef - Flexible Data Trimming Improves Performance of Global Machine Learning Methods in Omics-Based Personalized Oncology

Victor Tkachev, Maxim Sorokin, Constantin Borisov, Andrew Garazha, Anton Buzdin, Nicolas Borisov

International Journal of Molecular Sciences.2020; 21(3): 713. CrossRef - Phthalates exposure and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in children: a systematic review of epidemiological literature

Sarva Mangala Praveena, Rusheni Munisvaradass, Ruziana Masiran, Ranjith Kumar Rajendran, Chu-Ching Lin, Suresh Kumar

Environmental Science and Pollution Research.2020; 27(36): 44757. CrossRef - ThicknessTool: automated ImageJ retinal layer thickness and profile in digital images

Daniel E. Maidana, Shoji Notomi, Takashi Ueta, Tianna Zhou, Danica Joseph, Cassandra Kosmidou, Josep Maria Caminal-Mitjana, Joan W. Miller, Demetrios G. Vavvas

Scientific Reports.2020;[Epub] CrossRef - Predictors of Flu Vaccination for Persons Living With HIV in Central Texas

Julie A. Zuñiga, Alexandra A. García, Jonathan Fordyce, Ya-Ching Huang, Jungmin Park, Jane D. Champion

Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care.2019; 30(5): 593. CrossRef - Type I, II, and III statistical errors: A brief overview

Parampreet Kaur, Jill Stoltzfus

International Journal of Academic Medicine.2017; 3(2): 268. CrossRef

Statistical notes for clinical researchers: Type I and type II errors in statistical decision

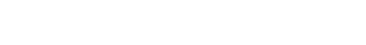

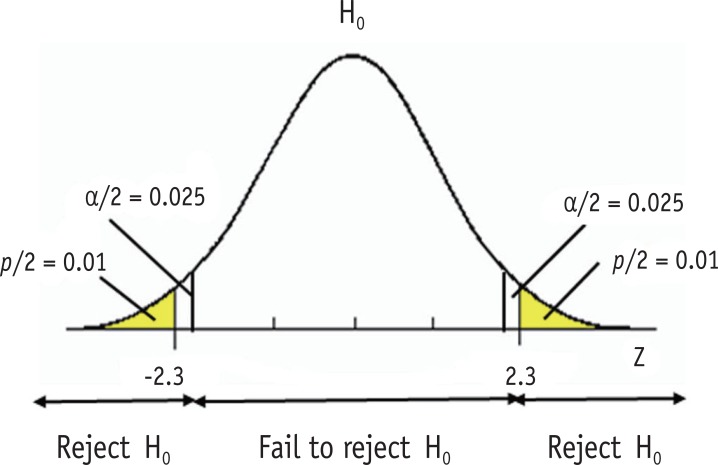

Figure 1 Illustration of type I (α) and type II (β) errors.

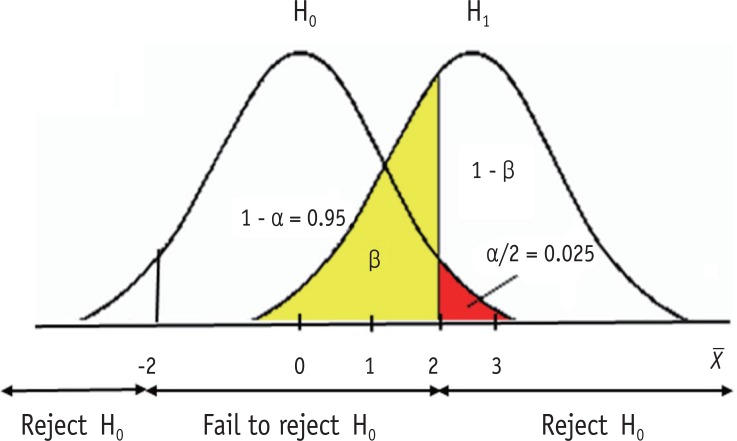

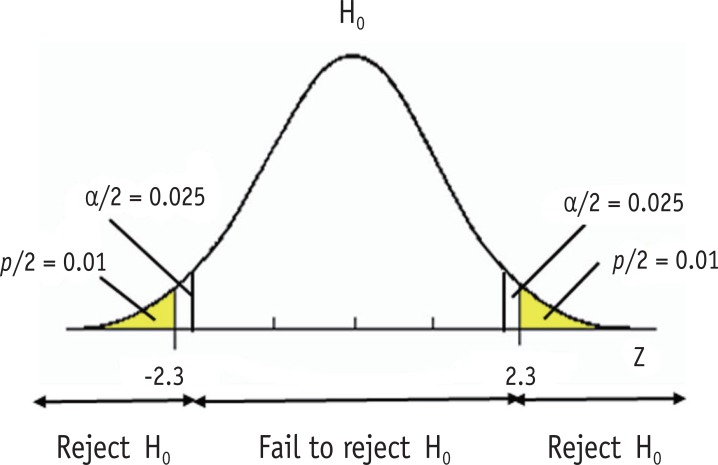

Figure 2 Significance level and p value.

Figure 1

Figure 2

Statistical notes for clinical researchers: Type I and type II errors in statistical decision

Possible results of hypothesis testing

| Conclusion based on data | Truth | |

|---|---|---|

| H0 True | H0 False | |

| Reject H0 | Type I error (α) | Correct conclusion (Power = 1 - β) |

| Fail to reject H0 | Correct conclusion (1 - α) | Type II error (β) |

Table 1 Possible results of hypothesis testing

KACD

KACD

ePub Link

ePub Link Cite

Cite