Abstract

-

Objectives

This study evaluated the marginal adaptation of ProRoot MTA (Dentsply Tulsa Dental), Biodentine (Septodont), and TotalFill BC RRM (FKG) placed in root-end cavities prepared with ultrasonic or Er,Cr:YSGG laser tips, using scanning electron microscopy.

-

Methods

The canals of 90 extracted maxillary central incisors were prepared and obturated and their roots resected. Six groups of 15 specimens were allocated as follows: ultrasonic + ProRoot MTA, ultrasonic + Biodentine, ultrasonic + TotalFill, laser + ProRoot MTA, laser + Biodentine, and laser + TotalFill. Roots were sectioned longitudinally to expose the filling material. Apical and coronal micrographs were taken, and the greatest distance between dentin and filling material was measured. The total gap area was also calculated using further micrographs.

-

Results

Cavities prepared with the ultrasonic tips and filled with Biodentine showed significantly greater gap dimensions compared with TotalFill (p < 0.001) and ProRoot MTA (p = 0.007) in the apical region. The ultrasonic group showed significantly higher void values compared to the laser group for ProRoot MTA (p = 0.026), when comparing the total values of void. The Biodentine group was significantly higher than the TotalFill group in root-end cavities prepared with ultrasonic tips (p < 0.001). The Biodentine group was significantly higher than the ProRoot MTA group in root-end cavities prepared with the laser tip (p = 0.002).

-

Conclusions

Under the conditions of this study, it was determined that the root-end cavity preparation technique had an effect on the amount of gaps formed between the dentin and the three filling materials.

-

Keywords: Dental marginal adaptation; Root-end cavity; Root-end filling; Ultrasonics

INTRODUCTION

Root canal treatment aims to eliminate bacteria from the root canal system and establish a barrier to prevent the passage of microorganisms or their products into the periapical tissues. Conventional treatment is successful in about 90% of cases [

1], but if treatment fails, retreatment is indicated. If this is impossible or not successful, periapical surgery may be suggested. This involves curettage of infected or inflamed tissue, resecting the infected or damaged root apex (apicectomy), preparation of a root-end cavity, and insertion of a restorative material to prevent communication between the canal system and the surrounding tissues [

2].

The resection is made perpendicular to the long axis of the root and 3 mm from its tip, as studies have shown this reduces 98% of the apical ramifications and eliminates 93% of lateral canals [

2,

3]. Ideally, the root-end cavity is at least 3 mm deep and anatomically parallel to the root outline. The cavity is prepared with burs, more recently, ultrasonic and laser tips [

2,

3]. Bur use can cause problems such as nonparallel cavity walls, palatal/lingual dentin perforation, and difficulty reaching the root tip [

3]. With ultrasonic tips, smaller, central, and parallel-walled cavities can be prepared, with less risk of perforation [

4]. Laser systems are also used in apical surgery. Many studies reported that the erbium laser used for apicectomy resulted in a high success rate with significant clinical benefits [

5–

8]. Amalgam, glass ionomer cement (GIC), zinc oxide-eugenol, composite resins, and bioceramics have all been used as root-end filling materials [

2]. Mineral trioxide aggregate (MTA) (e.g., ProRoot MTA; Dentsply Tulsa Dental, Tulsa, OK, USA) is a widely used material with excellent sealing ability and biocompatibility; however, it has a long setting time and complex handling characteristics [

9]. Biodentine (Septodont, Saint Maur des Fossés, France) is a tricalcium silicate-based cement that was introduced as a dentin substitute. It has good sealing properties and a short setting time [

10]. TotalFill BC RRM (FKG, La Chaux‐de‐Fonds, Switzerland) is a bioceramic material that, in premixed putty form, is very easy to use. It has good antibacterial properties due to its high pH, but it has a long setting time [

11].

Adaptation has been defined as the degree of proximity and interlocking of a filling material to the cavity wall. Good adaptation will reduce microleakage. It can be assessed by dye, radioisotope, bacterial penetration, scanning electron microscopy (SEM), and electrochemical methods, and with a fluid filtration technique [

12]. SEM provides high magnification and resolution and has been preferred in research evaluating marginal adaptation [

13,

14].

Main contributions of this study are: (1) the comparison of the amount of gaps created by three different root-end filling materials placed in cavities prepared with two different root-end preparation techniques using SEM; (2) during the evaluation, the largest distance measurements were made at ×150 magnification in both the apical and coronal parts of the cavity; (3) the calculation of total gap measurements using the ImageJ program (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA) on images taken at ×34 magnification. The null hypothesis was that there would be differences in gap formation depending on the type of root-end preparation and filling materials.

METHODS

The study was ethically approved by the ethics committee of Kocaeli University (KOU GOKAEK 2017/217). The study was performed in accordance with the ethical standards as laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki. Informed consent (including for publication) was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

According to a power analysis (G*Power ver. 3.1.9.4; Heinrich Heine University Düsseldorf, Düsseldorf, Germany) with a 0.05 level and 80% power (effect size, 0.40), the total sample size was found to be 90 (n = 15 for each group). Ninety extracted human maxillary central incisor teeth were used. The teeth had been extracted following appropriate consent procedures and were from hospital dental department collections. Teeth with similar root diameter and length, straight roots, complete root development, and no previous root canal treatment were used. Roots with resorption, fractures, open apices, or invisible canals were excluded. The teeth were cut to a root length of 15 mm. Canal patency was established by passing a size 15 K-file (Dentsply Maillefer, Ballaigues, Switzerland) through the apical foramen, from which 0.5 mm was subtracted to obtain the working length.

The root canals were prepared with ProTaper Next instruments (Dentsply Maillefer) using a VDW SILVER endomotor (VDW GmbH, Munich, Germany). The apical foramen was enlarged to an X4 (0.40/.06) instrument. The canals were irrigated with 1 mL of 2.5% NaOCl between instruments, and a final irrigation protocol (17% ethylenediamine tetraacetic acid and then 2.5% NaOCl) was used. The canals were dried with paper points (Dentsply Maillefer) and obturated with gutta-percha (Diadent, Cheongju, Korea) and AHPlus sealer (Dentsply-DeTrey, Konstanz, Germany) using lateral condensation. After obturation, the teeth were stored in an incubator at 37°C and 100% humidity for 1 week to ensure the setting of the sealer. The apical 3 mm of the roots were then resected perpendicular to the long axis with a cylindrical diamond bur (G837/010, DIA.TESSIN; Vanetti SA, Gordevio, Switzerland) at high speed under continuous air/water spray, and the roots were randomly assigned to six groups:

1. US + MTA: root-end cavity preparation with ultrasonic tip, ProRoot MTA root-end filling material

2. US + Biodentine: cavity preparation with ultrasonic tip, Biodentine filling material

3. US + TotalFill: cavity preparation with ultrasonic tip, TotalFill BC RRM filling material

4. Laser + MTA: cavity preparation with laser, ProRoot MTA filling material

5. Laser + Biodentine: cavity preparation with laser, Biodentine filling material

6. Laser + TotalFill: cavity preparation with laser, TotalFill BC RRM filling material

The 3-mm-deep and approximately 1 mm diameter root-end cavities were prepared using ultrasonic and laser tips under 2.5× loupe magnification (Carl Zeiss EyeMag Smart; Carl Zeiss Meditec AG, Jena, Germany) with illumination (Schott AG, Mainz, Germany). A periodontal probe (PCPUNC15; Hu-Friedy, Chicago, IL, USA) helped ensure a standard 3-mm depth.

Ultrasonic preparations involved an electro-medical system unit (EMS miniMaster Piezon; EMS SA, Nyon, Switzerland) with diamond-coated retro tips (DT-060 Berutti; EMS SA, Le Sentier, Switzerland) at medium power, “Endo” mode [

15], and maximum water coolant. Laser preparations were performed using an Er,Cr:YSGG laser (Waterlase iPlus/MD Gold; Biolase Inc., Foothill Ranch, CA, USA) with a power setting of 3.5 W, a pulse frequency of 20 Hz, 55% water, and 65% air [

15]. A tool with a diameter of 600 mm and a 6-mm MGG6 sapphire tip was used in noncontact mode. Ultrasonic and laser tips were changed after every five teeth, and the preparations were irrigated with saline and dried with paper points.

Filling materials were mixed according to the manufacturer’s instructions. ProRoot MTA was mixed with a powder-to-water ratio of 3:1. Biodentine was mixed with five drops of liquid added to the powder in the capsule and prepared by amalgamator for 30 seconds. TotalFill BC RRM was in ready-mixed putty form. The MTA was taken to the cavities using a 1.2-mm carrier (MTA+ Applicator; PPH Cerkamed, Stalowa Wola, Poland), and materials were placed with straight condensers and a VA10 flat plastic (G. Hartzell & Son, Concord, CA, USA). All procedures were conducted by the same operator.

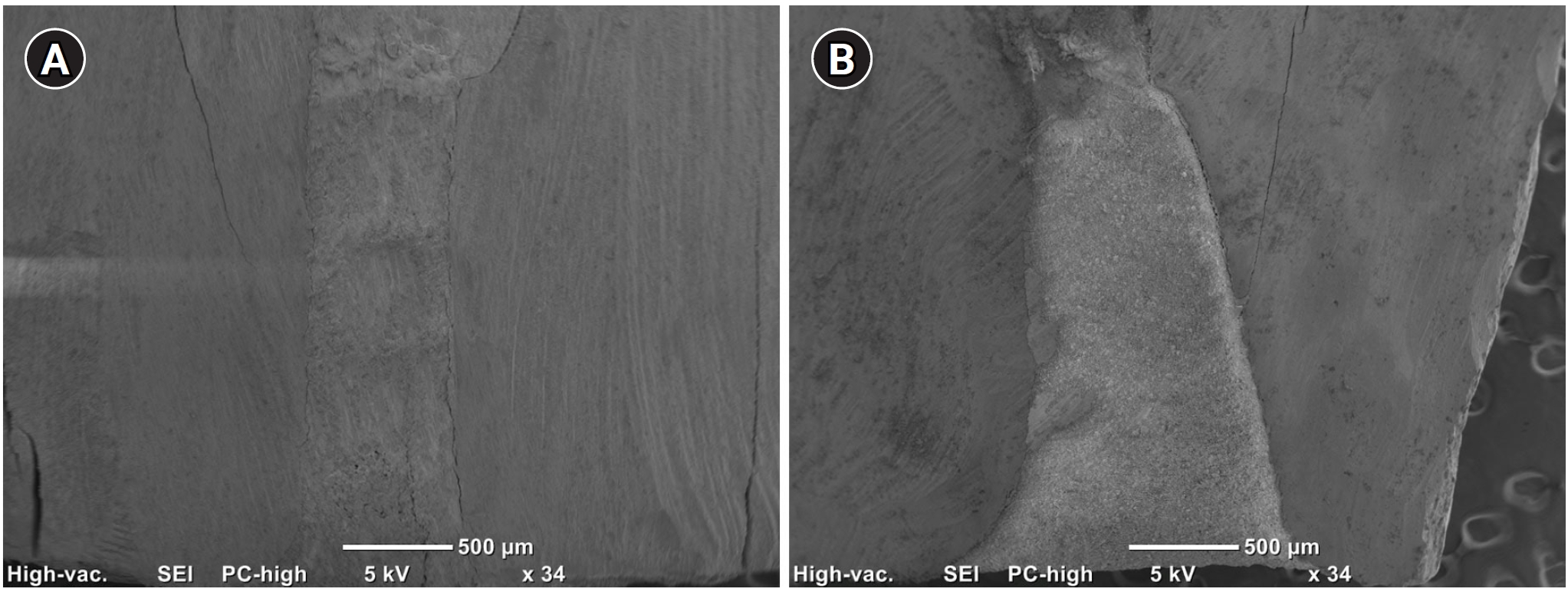

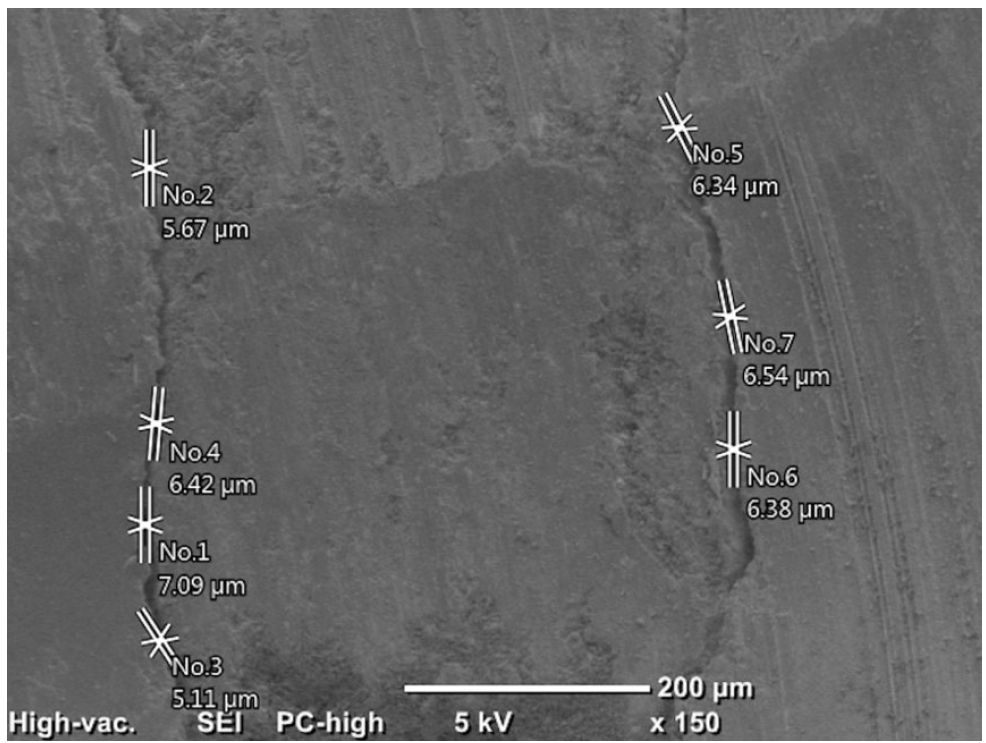

After setting, the roots were prepared longitudinally with burs and with super-fine abrasive paper (400–600 grit) to expose the filling materials, which were viewed under a dental operating microscope. Then the specimens were prepared for SEM (JEOL JCM 6000 Plus; JEOL, Tokyo, Japan). The specimens were dehydrated in ethanol and dried in open air. After drying, each half was mounted on an aluminum stub and sputter-coated with gold at 2 mA and 30 seconds (Cressington 108auto sputter coater; Cressington Scientific Instruments Ltd., Watford, London, UK).

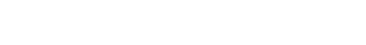

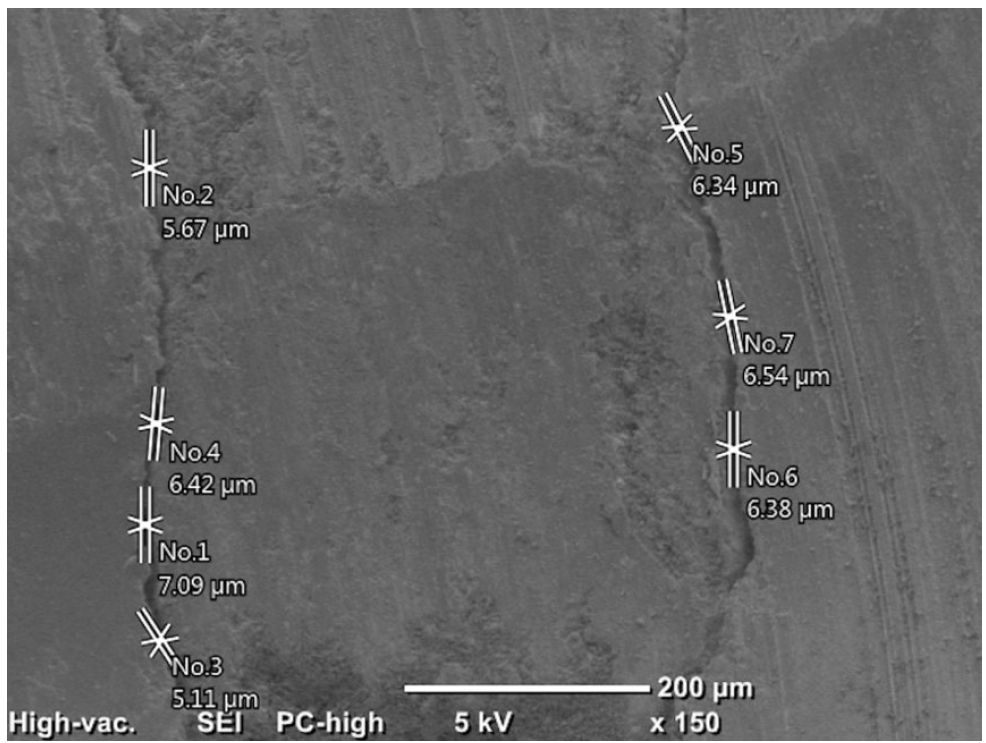

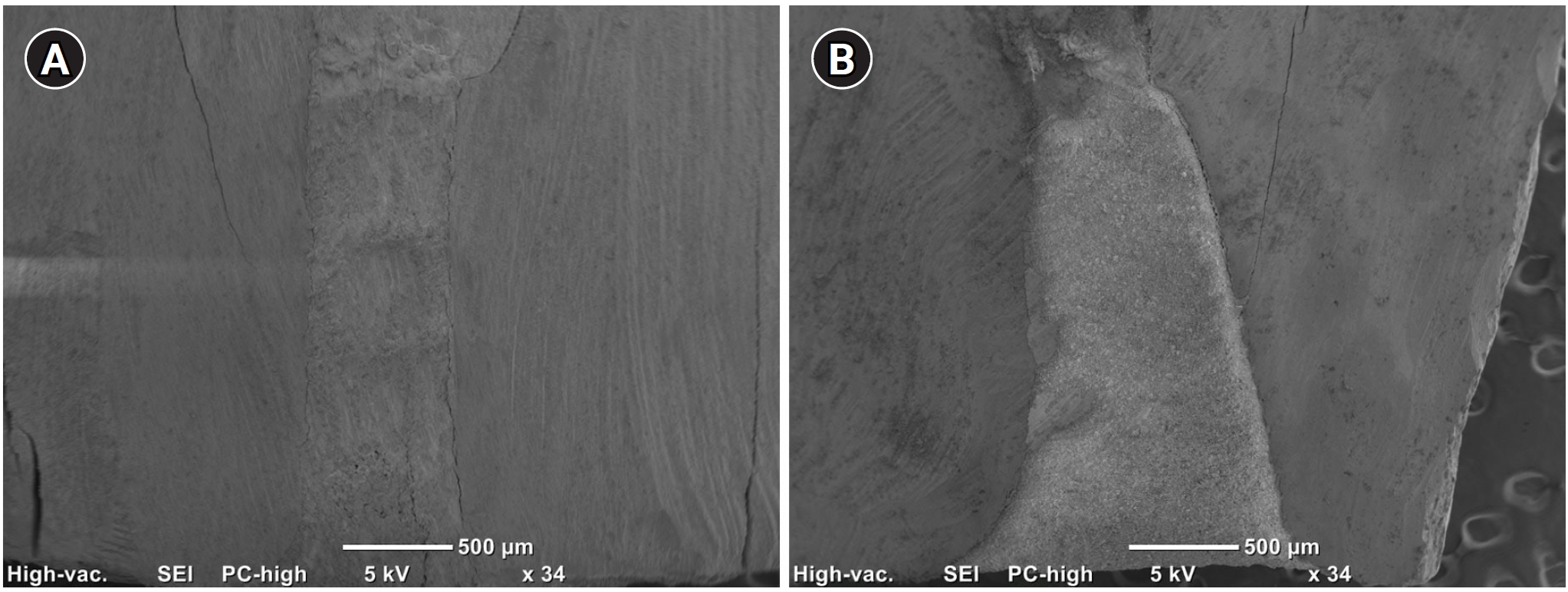

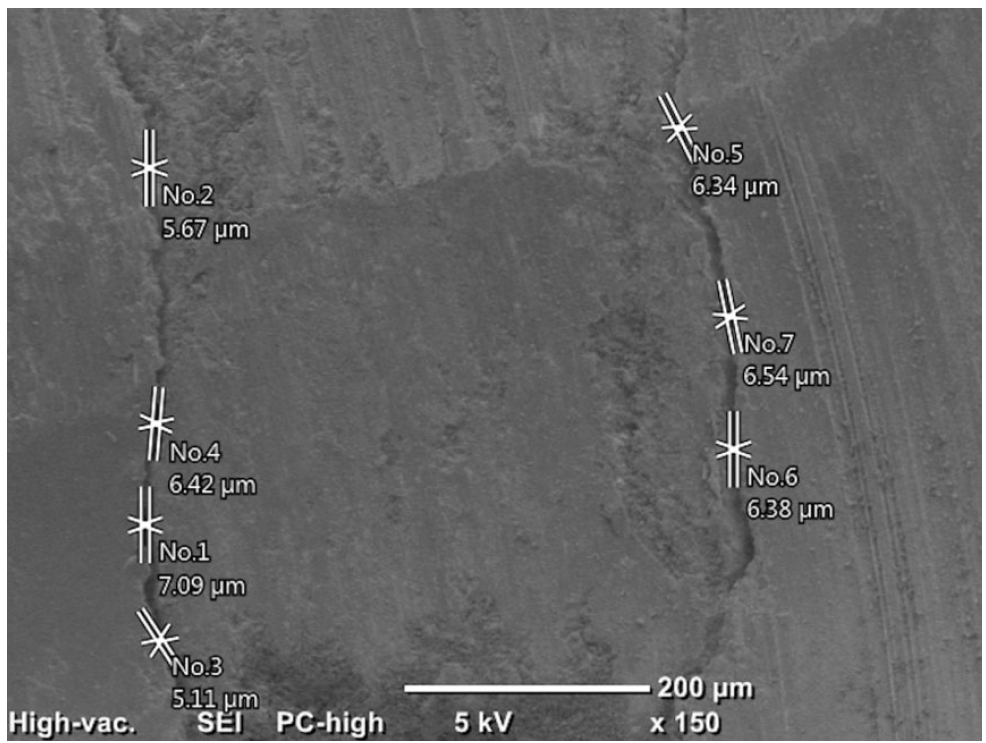

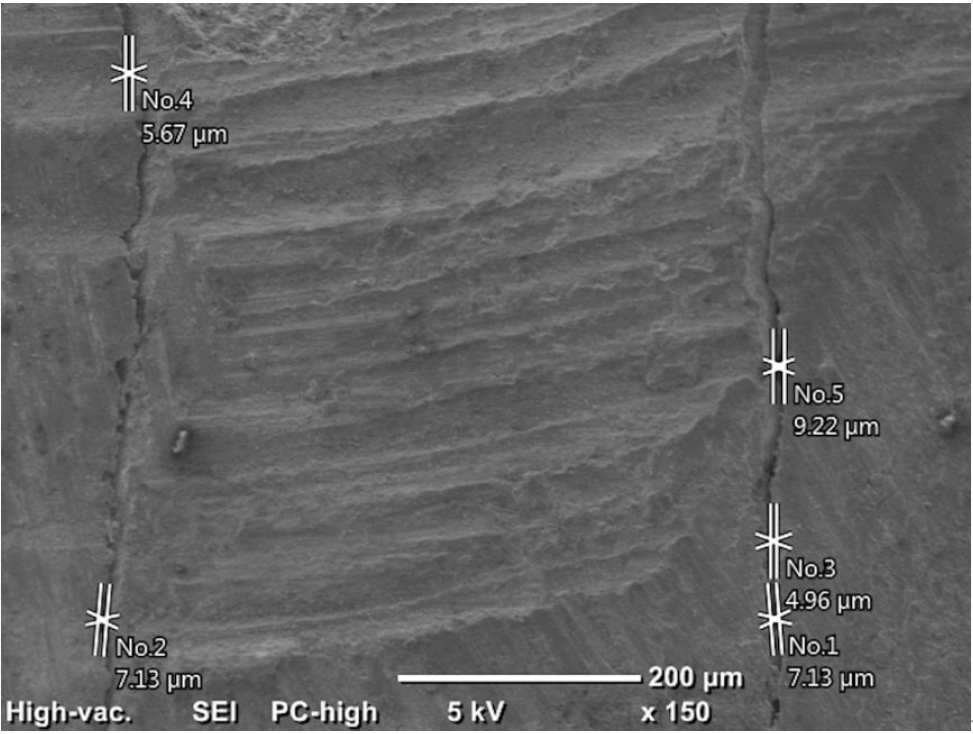

Initially, the distances between the filling materials and cavity walls were measured directly using the SEM (150×) at two points (apical and coronal) of the material/dentin interface. It was recorded as 0 in areas with no gap, and the maximum values were recorded in the apical and coronal regions (

Figures 1 and

2).

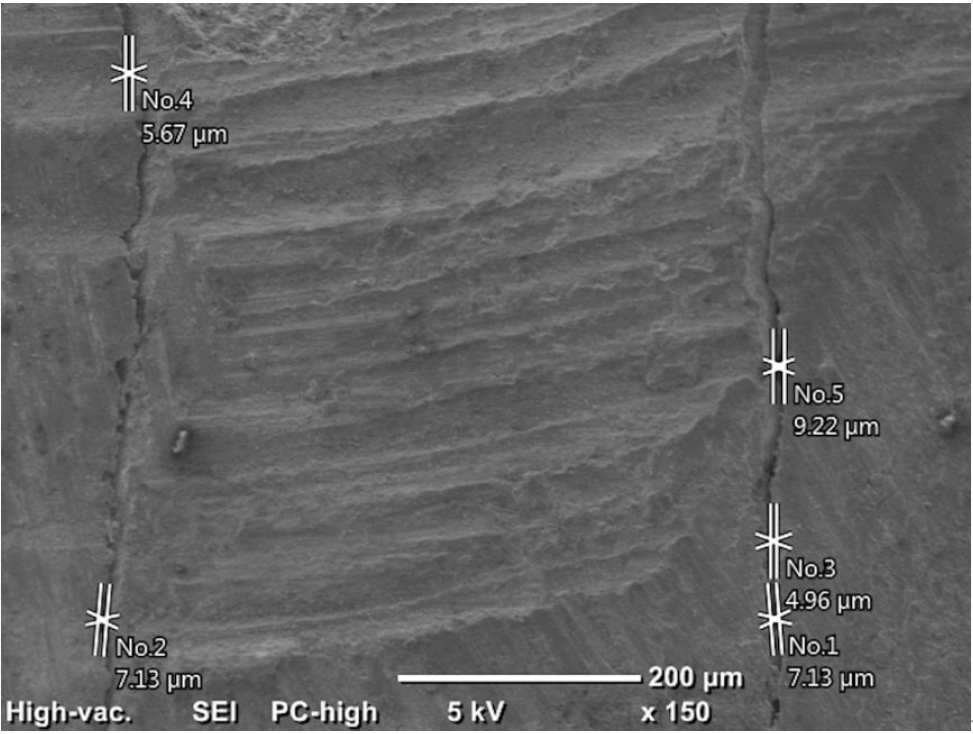

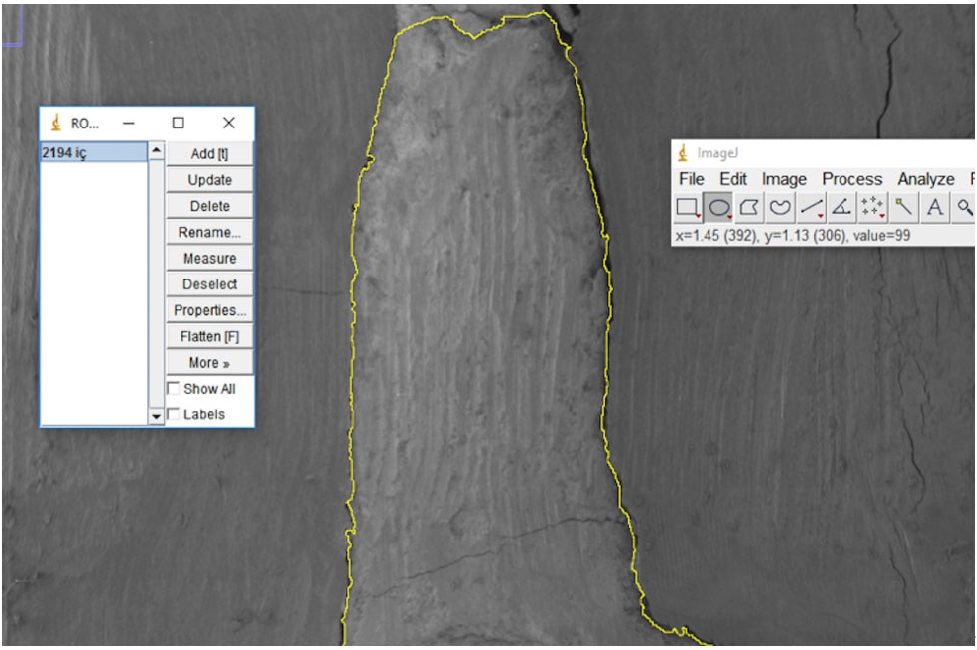

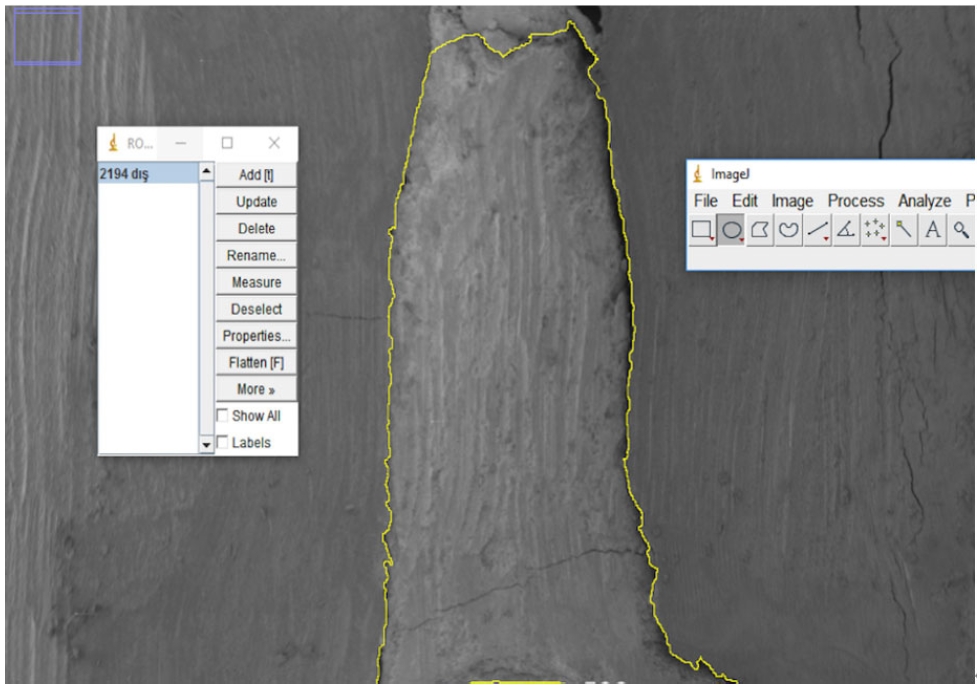

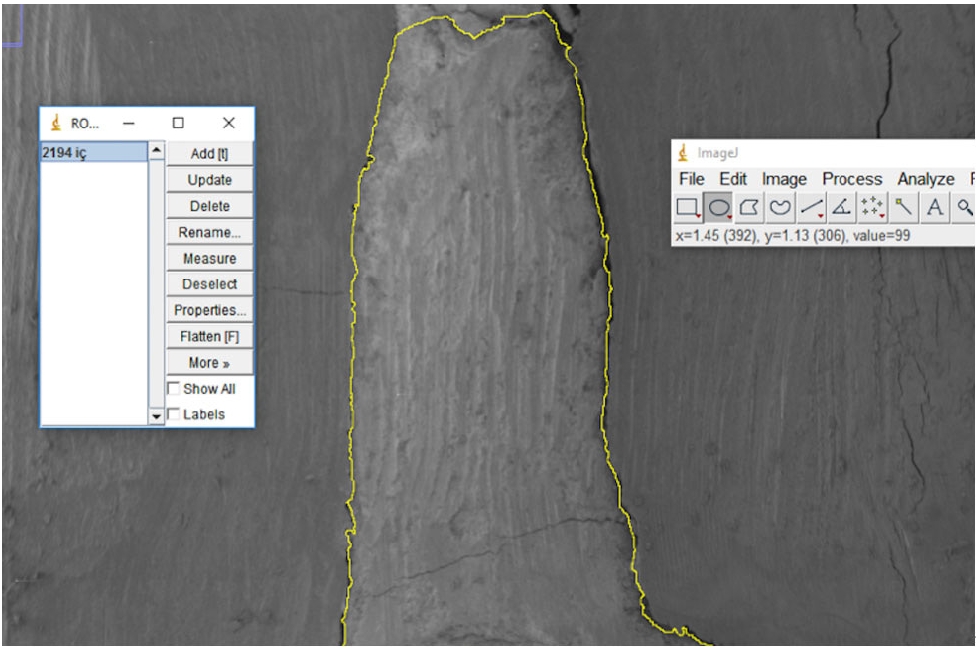

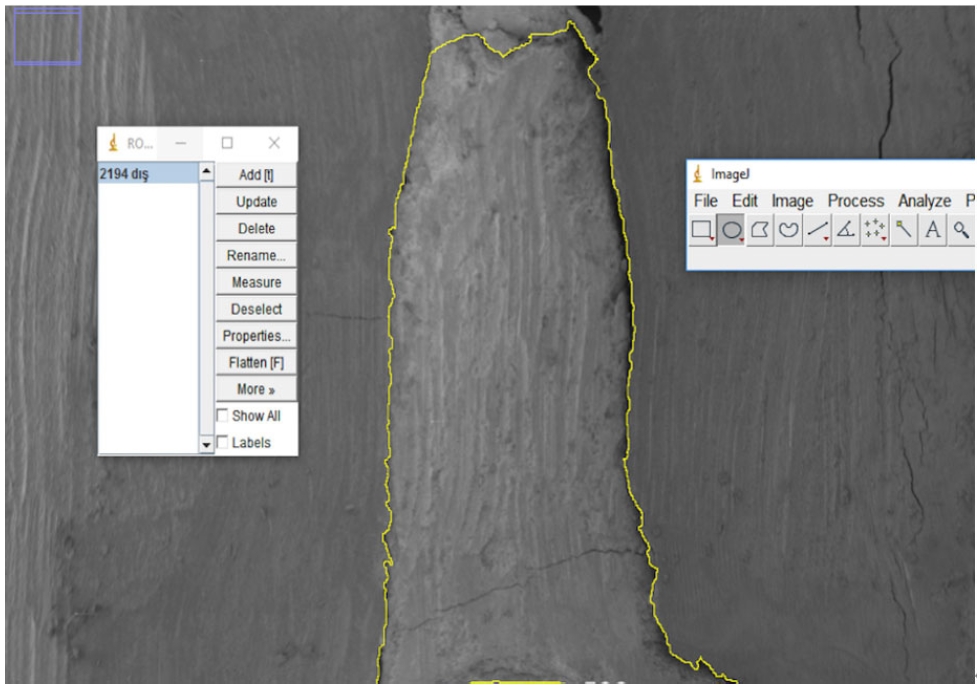

Next, electron micrographs were obtained at 34× magnification for analysis (ImageJ 1.52a). Calculations were made for each sample regarding the area of the gaps between the filling material and the surrounding structures (dentin and gutta-percha). First, micrographs of the 90 roots were transferred to the computer as JPEGs and opened in ImageJ. Then, the outer surface area of the cavity was scanned with the Selection/Add to Manager tool (

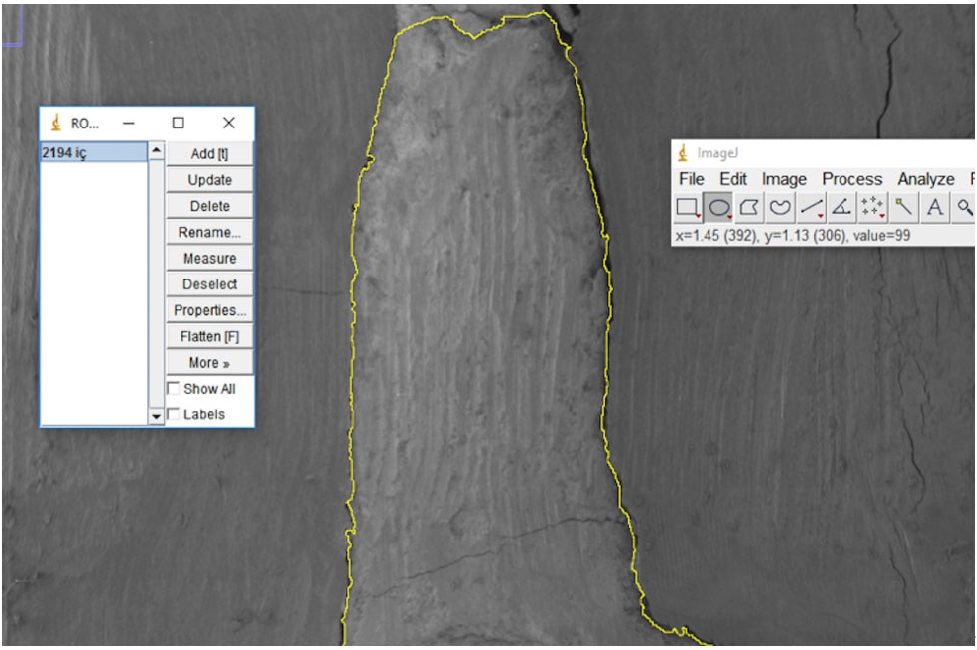

Figure 3). The scanning process was also carried out for the filling material surface area (

Figure 4). By calculating the difference between the two areas, the void area between the material and the cavity can be determined.

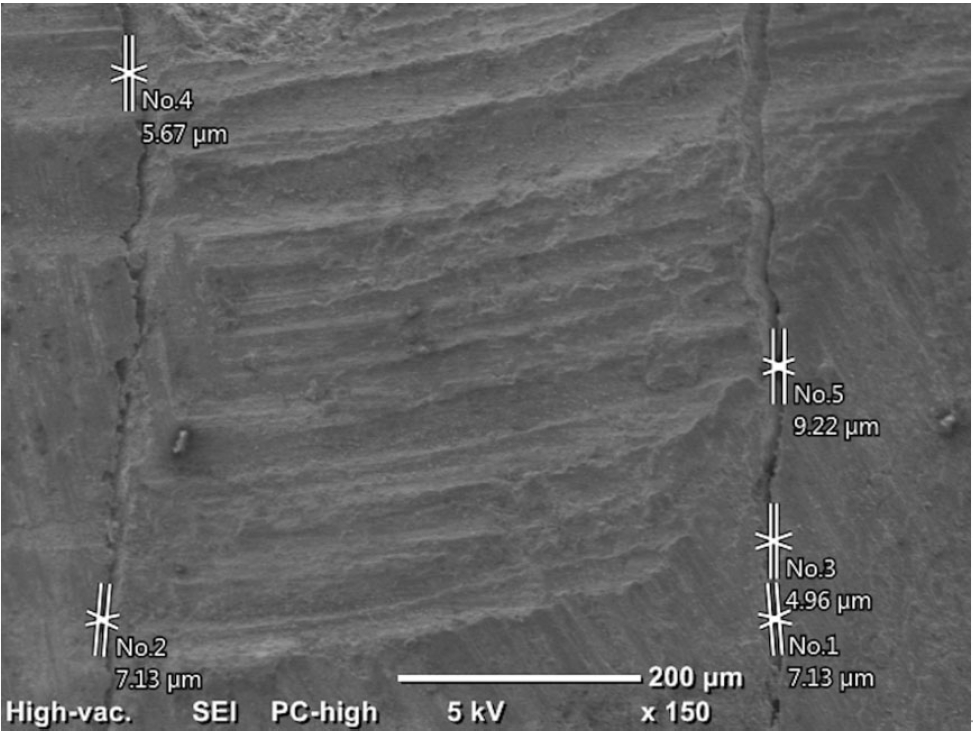

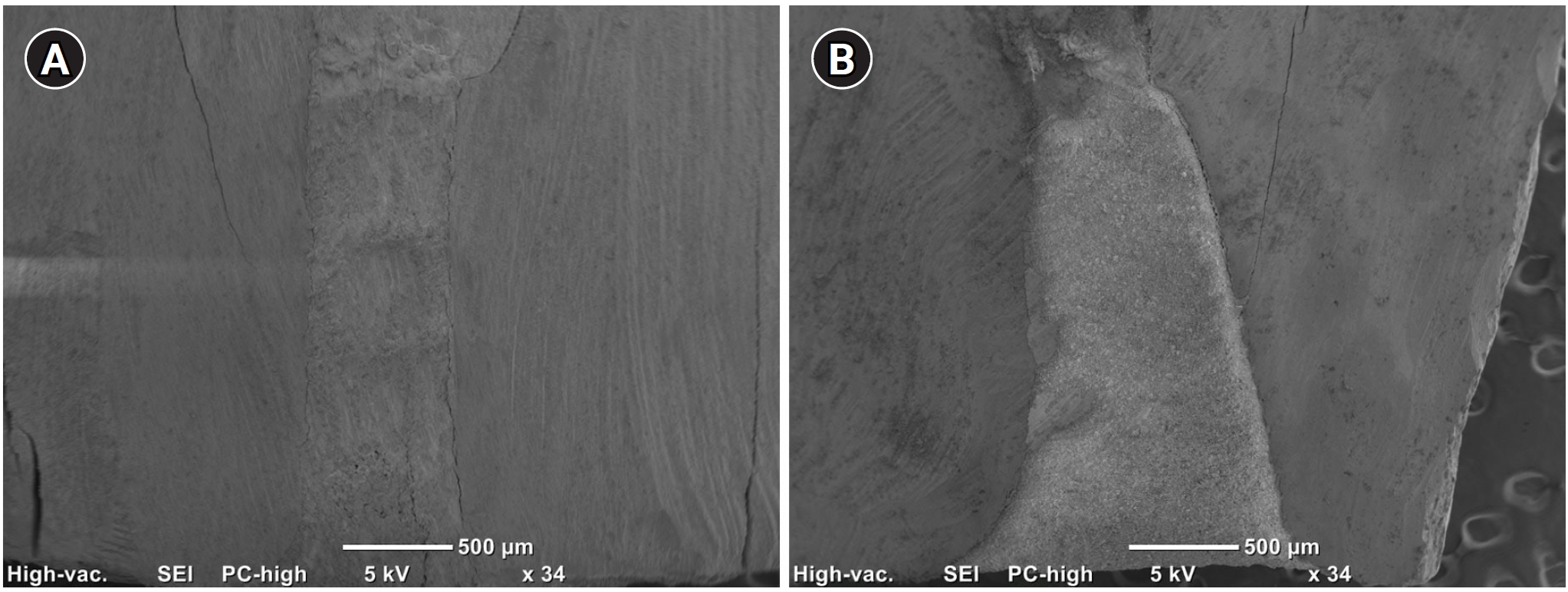

Figure 5 shows an example of cavities prepared with the two devices and filled with ProRootMTA.

NCSS (Number Cruncher Statistical System) 2007 (NCSS LLC, Kaysville, UT, USA) was used for statistical analysis. The suitability of quantitative data for normal distribution was tested using the Shapiro-Wilk test and graphical analysis. An independent groups t-test was used to compare normally distributed quantitative variables between two groups, and the Mann-Whitney U test was used to compare non-normally distributed quantitative variables between two groups. Kruskal-Wallis and Dunn-Bonferroni post-hoc tests were used to compare non-normally distributed quantitative variables between more than two groups. Statistical significance was accepted as p < 0.05.

RESULTS

Table 1 shows the maximum distances between filling materials and dentin in the apical and coronal regions (μm).

Table 2 shows a comparison of the maximum distance measurement values between root-end filling material and dentin at the coronal and apical regions between groups (μm). The ultrasonic group was significantly higher than the laser group for Biodentine coronally (

p = 0.016). The Biodentine group was significantly higher than the TotalFill group in root-end cavities prepared with ultrasonic tips (

p = 0.001). There was no significant difference between groups in the laser cavities (

p > 0.05). The ultrasonic group was significantly higher than the laser group for Biodentine apically (

p = 0.001). Biodentine showed significantly greater gap dimensions compared with TotalFill (

p < 0.001) and ProRoot MTA (

p = 0.007). There was no significant difference among groups in the laser-prepared cavities (

p > 0.05).

Table 3 shows the total void area values (mm

2) between root-end filling material and dentin calculated using ImageJ software.

Table 4 shows a comparison of the total values (mm

2) of voids among groups. The ultrasonic group was significantly higher than the laser group for ProRoot MTA (

p = 0.026). The Biodentine group was significantly higher than the TotalFill group in root-end cavities prepared with an ultrasonic tip (

p < 0.001). The Biodentine group was significantly higher than the ProRoot MTA group in root-end cavities prepared with the laser tip (

p = 0.002). There was no significant difference between the TotalFill and Biodentine groups and the TotalFill (

p = 0.744) and ProRoot MTA groups (

p = 0.071) (

Table 4).

DISCUSSION

Marginal adaptation has been defined as the degree of closeness of the filling material to the cavity wall and its interdigitation [

12]. Problems with the adaptation might lead to treatment failure [

16]. Microcracks on the dentin surface, which adversely affect the adaptation process, might occur during ultrasonic cavity preparation [

17]; however, this is not a universal finding [

18]. Reduction in microcrack formation has been reported at low-to-medium ultrasonic power settings and when using diamond-coated tips [

17]. Hence, a medium power setting with diamond-coated tips was preferred in this study. It has been reported that there is no difference in the frequency of microcrack formation when ultrasonic tips and Er:YAG laser are compared [

19]. However, in another study, microcrack formation has been observed using ultrasonics, and none has been observed using Er,Cr:YSGG laser [

20]. Er,Cr:YSGG laser was also used for root-end preparations to compare the effect of the root-end cavity preparation type on the marginal adaptation in this study.

Several techniques can be used to evaluate the adaptation provided by root-end filling materials and the quality of apical sealing [

12]. SEM was used as it provides high magnification and good resolution in this study [

13]. However, dehydration and exposure to high vacuum during specimen preparation may lead to cracks or shrinkage in dentin or filling material. To eliminate this, resin replicas can be used. Torabinejad

et al. [

21] found similar results in a related study using this method, but it would have been exhaustive for 90 teeth, and another study has been done without replicas [

13,

22]. Sections were generally obtained with diamond separators or burs, where forces and vibrations may cause the filling materials to be damaged or displaced [

23]. To overcome this, guiding notches on the root surfaces were cut with a diamond separator, about 1 mm away from the root-end material. The thin dentin layer was then removed under the dental operating microscope by careful sanding.

Gondim

et al. [

14] stated that quantitative analysis based on measurement provides more objective and reliable results. The images were taken at two different magnifications: 34× and 150×. The maximum value was recorded from the distance measurements between dentin and filling material on micrographs taken at the apical 1 mm and coronal 1 mm at 150× magnification. For the micrographs at 34×, quantitative measurements were made by calculating the area with ImageJ.

For Biodentine, the gap formation in the ultrasonic group was significantly higher than in the laser group. In contrast, the other two materials did not show a significant difference between cavity techniques. In the area measurements of gaps using the ImageJ program, the ultrasonic group for ProRoot MTA was significantly higher than the laser group. This may be explained by the fact that the use of an Er,Cr:YSGG laser can increase the mechanical bonding between the dentin wall and root-end material by forming micro retentive areas and by removing the smear layer [

24,

25]. The difference in the results of these two measurement methods may be because when calculating the total area of the voids in the root-end cavity with the ImageJ program, the highest single distance measurement between the filling material and dentin on the SEM images taken from the apical and coronal regions was taken into account.

Using SEM, Xavier

et al. [

22] examined the marginal adaptation of MTA Angelus (Angelus, Londrina, Brazil), Super-EBA (Bosworth, Skokie, IL, USA), and Vitremer (3M ESPE, St. Paul, MN, USA) in ultrasonically prepared cavities. Gap measurements of two different sections having 1 mm thickness, taken horizontally at 1 and 2 mm from the apex, were made at four different points under SEM. A study by Torabinejad

et al. [

21] prepared cavities using fissure burs and used MTA, amalgam, Super-EBA, and IRM (Dentsply Sirona, York, PA, USA) as fillings and examined marginal adaptation with SEM. Replicas of the vertical cuts of the samples were made with resin, and the gaps of both the teeth and the replicas were examined at four different points. However, the maximum values were recorded in the apical and coronal regions in this study in accordance with Soundappan

et al. [

26]. The cavities were prepared ultrasonically, and Biodentine, MTA, and IRM were used as filling materials. Two horizontal sections were taken, 1 and 2 mm from the apex. The horizontal sections were divided into four equal parts, and under 1,000× magnification, the most significant gaps were measured in each quarter. The greatest gap formation was seen in Biodentine, and the least in the MTA group. In contrast, in this study, more gap formation was detected in the Biodentine group compared to the MTA group. Ravi Chandra

et al. [

27] examined the marginal adaptation of a GIC, MTA, and Biodentine in ultrasonically prepared cavities using confocal laser scanning microscopy. Better marginal adaptation was detected in the Biodentine group than in GIC and MTA. The differences between the results of this study may be due to the differences in imaging technique and the section examined.

Khandelwal

et al. [

28] used dye penetration to examine microleakage of Biodentine and MTA in root-end cavities prepared using a conventional drill and ultrasonic tip. The greatest amount of microleakage was observed in MTA in cavities opened with a bur. Biodentine’s high-quality sealing properties were associated with the creation of an alkaline caustic effect when the hydration products of calcium silicate cement come in contact with dentin and dissolve the collagen structure at the dentin interface. This effect results in the formation of a tag-like structure called ‘mineral infiltration zone,’ and with its adaptation ability due to its smaller particle size. Han and Okiji [

29] showed that the uptake of calcium and silicon ions into dentin, which leads to these tag-like structures, was higher in Biodentine compared to MTA. In addition, its short hardening time, ease of manipulation, non-discolouration, and good sealing properties lead to Biodentine being a preferred material [

10,

26].

TotalFill RRM was introduced under the trade name EndoSequence RRM (Brasseler USA Dental, Savannah, GA, USA) as a premixed bioceramic root-end filling material. TotalFill and EndoSequence have the same properties and form [

30]. Endodontic bioceramics are not sensitive to moisture and blood. They are dimensionally stable and expand slightly on setting. The initial setting time of MTA and TotalFill BC RRM putty is approximately 3 to 4 hours, while the setting time of Biodentine is approximately 10 to 12 minutes. Handling properties of TotalFill BC RRM putty are better than others [

11].

Alanezi

et al. [

31] examined the bacterial microleakage of EndoSequence BC RRM and ProRoot MTA using

Enterococcus faecalis. The materials were placed in cavities prepared using a KiS ultrasonic tip. No difference was observed between the fillings. Shokouhinejad

et al. [

32] examined the marginal adaptations of EndoSequence RRM putty, EndoSequence RRM paste, and ProRoot MTA in ultrasonically prepared cavities using SEM. After hardening, replicas of the horizontal and vertical sections of the teeth were taken. No significant difference was observed between the groups for the horizontal cross-section. In the vertical section, EndoSequence paste was reported to have significantly more voids. Lertmalapong

et al. [

33] examined the marginal adaptation of ProRoot MTA, RetroMTA, Biodentine, and TotalFill BC RRM’s putty and paste forms in the treatment of teeth with open apices, placing materials at two different levels of thickness, 3 and 4 mm. Resin replicas were made and imaged with SEM, and then studied with the ImageJ program. Biodentine, TotalFill BC RRM putty, and 4 mm ProRoot MTA groups had fewer voids than the other groups. However, the external surface area of the cavity and the surface areas of the filling materials were measured separately and then calculated by taking the differences in this study, and the cavities opened ultrasonically had a greater void area in the Biodentine group than in the TotalFill group.

CONCLUSIONS

Under the conditions of this in vitro study, when evaluating total void, choosing a laser instead of ultrasound for root-end preparation resulted in a smaller gap between material and dentin if MTA was used. When the root-end cavity was prepared with ultrasonics, it was observed that more gap formation occurred with Biodentine compared to TotalFill; when the cavity was prepared with laser, it was observed that more gap formation occurred with Biodentine compared to MTA. Further clinical studies are needed to evaluate the success of different root-end preparation techniques and filling materials.

-

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

-

FUNDING/SUPPORT

The authors have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

-

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conceptualization: Zengin B, Aydemir S. Data curation, Investigation, Project administration: Zengin B. Formal analysis: all authors. Methodology: Aydemir S. Writing - original draft: all authors. Writing - review & editing: all authors. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

-

DATA SHARING STATEMENT

All data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its supplementary materials.

Figure 1.An example of measurements made at the coronal region under 150× magnification.

Figure 2.An example of measurements made at the apical region under 150× magnification.

Figure 3.Scanning of the cavity outer surface area.

Figure 4.Scanning the filling material surface area.

Figure 5.Micrographs of ProRoot MTA ultrasonic (A) and laser (B) samples under 34× magnification. ProRoot MTA: Dentsply Tulsa Dental, Tulsa, OK, USA.

Table 1.Maximum distance values between material and dentin at the apical and coronal regions for the six groups (μm)

|

No. |

US + MTA group

|

US + Biodentine group

|

US + TotalFill group

|

Laser + MTA group

|

Laser + Biodentine group

|

Laser + TotalFill group

|

|

Coronal |

Apical |

Coronal |

Apical |

Coronal |

Apical |

Coronal |

Apical |

Coronal |

Apical |

Coronal |

Apical |

|

1 |

4.26 |

5.72 |

6.73 |

10.70 |

2.92 |

3.55 |

10.10 |

13.80 |

5.16 |

5.67 |

10.30 |

8.77 |

|

2 |

4.96 |

7.45 |

7.23 |

18.30 |

0.00 |

7.09 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

4.26 |

4.93 |

7.23 |

11.90 |

|

3 |

14.90 |

21.20 |

5.01 |

9.52 |

4.76 |

7.09 |

0.00 |

8.58 |

4.09 |

7.74 |

2.13 |

0.00 |

|

4 |

5.85 |

5.67 |

7.93 |

5.16 |

3.17 |

3.55 |

7.93 |

6.78 |

7.14 |

6.47 |

4.49 |

6.42 |

|

5 |

5.01 |

7.67 |

5.85 |

8.63 |

5.05 |

8.96 |

6.02 |

5.42 |

8.76 |

11.9 |

5.16 |

12.40 |

|

6 |

9.54 |

9.22 |

21.50 |

16.50 |

4.62 |

2.92 |

7.37 |

11.00 |

3.66 |

4.91 |

5.16 |

3.62 |

|

7 |

6.69 |

7.09 |

10.70 |

20.30 |

17.80 |

3.82 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

9.23 |

9.53 |

7.09 |

11.50 |

|

8 |

3.01 |

7.80 |

10.70 |

10.70 |

2.48 |

19.30 |

7.52 |

7.23 |

5.01 |

4.26 |

8.27 |

5.16 |

|

9 |

5.01 |

5.67 |

3.82 |

8.77 |

4.90 |

5.16 |

7.93 |

8.10 |

5.18 |

5.18 |

4.54 |

5.40 |

|

10 |

4.98 |

5.18 |

4.96 |

7.91 |

5.01 |

6.26 |

3.82 |

0.00 |

5.73 |

4.41 |

3.84 |

9.25 |

|

11 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

11.50 |

31.50 |

3.19 |

2.70 |

7.14 |

2.66 |

10.8 |

11.9 |

3.55 |

4.26 |

|

12 |

6.38 |

7.23 |

12.10 |

26.30 |

4.96 |

7.09 |

6.03 |

6.63 |

9.00 |

10.4 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

|

13 |

5.67 |

7.23 |

8.09 |

8.92 |

3.55 |

3.62 |

5.21 |

8.75 |

5.49 |

5.16 |

7.98 |

6.65 |

|

14 |

17.7 |

4.49 |

22.00 |

22.20 |

2.48 |

3.27 |

4.26 |

5.73 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

4.98 |

5.18 |

|

15 |

5.72 |

7.93 |

11.20 |

11.50 |

17.09 |

7.83 |

3.55 |

7.13 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

2.92 |

4.62 |

Table 2.Comparison of the maximum distance measurement values between root-end filling material and dentin at the coronal and apical regions among groups (μm)

|

Region and method |

Total |

TotalFill |

Biodentine |

MTA |

p-valuea)

|

p-valueb)

|

|

TotalFill vs Biodentine |

TotalFill vs MTA |

Biodentine vs MTA |

|

Coronal |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

US |

5.05 (4.62–9.054) |

4.62 (2.92–5.01) |

8.09 (5.85–11.5) |

5.67 (4.96–6.69) |

0.002**

|

0.001**

|

0.269 |

0.205 |

|

Laser |

5.16 (3.82–7.37) |

4.98 (3.55–7.23) |

5.18 (4.09–8.76) |

6.02 (3.55–7.52) |

0.836 |

0.999 |

0.999 |

0.999 |

|

p-valuec) (US vs laser) |

0.281 |

0.367 |

0.016*

|

0.87 |

|

|

|

|

|

Apical |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

US |

7.45 (5.18–9.52) |

5.16 (3.55–7.09) |

10.7 (8.77–20.3) |

7.23 (5.67– 7.8) |

<0.001**

|

<0.001**

|

0.703 |

0.007**

|

|

Laser |

5.73 (4.41–8.75) |

5.4 (4.26–9.25) |

5.18 (4.41–9.53) |

6.78 (2.66–8.58) |

0.917 |

0.999 |

0.999 |

0.999 |

|

p-valuec) (US vs laser) |

0.055 |

0.486 |

0.001**

|

0.775 |

|

|

|

|

Table 3.Total void area values between root-end filling material and dentin calculated using ImageJ program (mm2)

|

No. |

US + MTA group |

US + Biodentine group |

US + TotalFill group |

Laser + MTA group |

Laser + Biodentine group |

Laser + TotalFill group |

|

1 |

0.008 |

0.008 |

0.003 |

0.016 |

0.024 |

0.015 |

|

2 |

0.014 |

0.030 |

0.004 |

0.046 |

0.009 |

0.003 |

|

3 |

0.054 |

0.020 |

0.008 |

0.011 |

0.029 |

0.004 |

|

4 |

0.009 |

0.034 |

0.005 |

0.007 |

0.013 |

0.005 |

|

5 |

0.012 |

0.011 |

0.011 |

0.015 |

0.040 |

0.008 |

|

6 |

0.008 |

0.019 |

0.006 |

0.003 |

0.031 |

0.007 |

|

7 |

0.012 |

0.018 |

0.006 |

0.018 |

0.020 |

0.001 |

|

8 |

0.008 |

0.035 |

0.013 |

0.007 |

0.019 |

0.009 |

|

9 |

0.023 |

0.008 |

0.013 |

0.031 |

0.016 |

0.007 |

|

10 |

0.001 |

0.008 |

0.010 |

0.013 |

0.015 |

0.001 |

|

11 |

0.000 |

0.065 |

0.006 |

0.005 |

0.026 |

0.002 |

|

12 |

0.009 |

0.049 |

0.006 |

0.004 |

0.023 |

0.022 |

|

13 |

0.003 |

0.010 |

0.004 |

0.051 |

0.016 |

0.004 |

|

14 |

0.010 |

0.026 |

0.005 |

0.010 |

0.002 |

0.002 |

|

15 |

0.006 |

0.023 |

0.017 |

0.006 |

0.003 |

0.008 |

Table 4.Comparison of total values (mm2) of void areas between dentin and filling material among groups

|

Total gap area |

Ultrasonic |

Laser |

p-valuec) (ultrasonic vs laser) |

|

Total |

0.010 (0.006–0.018) |

0.010 (0.005–0.019) |

0.671 |

|

TotalFill |

0.006 (0.005–0.011) |

0.011 (0.006–0.018) |

0.081 |

|

Biodentine |

0.020 (0.010–0.034) |

0.019 (0.013–0.024) |

0.486 |

|

MTA |

0.009 (0.008–0.012) |

0.005 (0.002–0.008) |

0.026 |

|

p-valuea)

|

0.001**

|

0.002**

|

|

|

p-valueb)

|

|

|

|

|

TotalFill vs Biodentine |

<0.001**

|

0.744 |

|

|

TotalFill vs MTA |

0.549 |

0.071 |

|

|

Biodentine vs MTA |

0.052 |

0.002**

|

|

REFERENCES

- 1. Lazarski MP, Walker WA, Flores CM, Schindler WG, Hargreaves KM. Epidemiological evaluation of the outcomes of nonsurgical root canal treatment in a large cohort of insured dental patients. J Endod 2001;27:791-796.ArticlePubMed

- 2. Gutmann JL. Surgical endodontics: past, present, and future. Endod Top 2014;30:29-43.Article

- 3. Kim S. Principles of endodontic microsurgery. Dent Clin North Am 1997;41:481-497.ArticlePubMed

- 4. Rotstein I, Ingle JI. Ingle’s endodontics. 7th ed. Raleigh, NC, USA: PMPH‑USA Ltd.; 2019.

- 5. Miserendino LJ. The laser apicoectomy: endodontic application of the CO2 laser for periapical surgery. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 1988;66:615-619.ArticlePubMed

- 6. Angiero F, Benedicenti S, Signore A, Parker S, Crippa R. Apicoectomies with the erbium laser: a complementary technique for retrograde endodontic treatment. Photomed Laser Surg 2011;29:845-849.ArticlePubMed

- 7. Komori T, Yokoyama K, Takato T, Matsumoto K. Clinical application of the erbium:YAG laser for apicoectomy. J Endod 1997;23:748-750.ArticlePubMed

- 8. Gouw-Soares S, Tanji E, Haypek P, Cardoso W, Eduardo CP. The use of Er:YAG, Nd:YAG and Ga-Al-As lasers in periapical surgery: a 3-year clinical study. J Clin Laser Med Surg 2001;19:193-198.ArticlePubMed

- 9. Torabinejad M, Watson TF, Pitt Ford TR. Sealing ability of a mineral trioxide aggregate when used as a root end filling material. J Endod 1993;19:591-595.ArticlePubMed

- 10. Rajasekharan S, Martens LC, Cauwels RG, Verbeeck RM. Biodentine™ material characteristics and clinical applications: a review of the literature. Eur Arch Paediatr Dent 2014;15:147-158.ArticlePubMedPDF

- 11. Trope M, Bunes A, Debelian G. Root filling materials and techniques: bioceramics a new hope? Endod Top 2015;32:86-96.Article

- 12. Torabinejad M, Lee SJ, Hong CU. Apical marginal adaptation of orthograde and retrograde root end fillings: a dye leakage and scanning electron microscopic study. J Endod 1994;20:402-407.ArticlePubMed

- 13. Küçükkaya Eren S, Görduysus MÖ, Şahin C. Sealing ability and adaptation of root-end filling materials in cavities prepared with different techniques. Microsc Res Tech 2017;80:756-762.ArticlePubMed

- 14. Gondim E, Zaia AA, Gomes BP, Ferraz CC, Teixeira FB, Souza-Filho FJ. Investigation of the marginal adaptation of root-end filling materials in root-end cavities prepared with ultrasonic tips. Int Endod J 2003;36:491-499.ArticlePubMedPDF

- 15. Batista de Faria-Junior N, Tanomaru-Filho M, Guerreiro-Tanomaru JM, de Toledo Leonardo R, Camargo Villela Berbert FL. Evaluation of ultrasonic and ErCr:YSGG laser retrograde cavity preparation. J Endod 2009;35:741-744.ArticlePubMed

- 16. Saunders WP, Saunders EM, Gutmann JL. Ultrasonic root-end preparation, Part 2. Microleakage of EBA root-end fillings. Int Endod J 1994;27:325-329.ArticlePubMed

- 17. Layton CA, Marshall JG, Morgan LA, Baumgartner JC. Evaluation of cracks associated with ultrasonic root-end preparation. J Endod 1996;22:157-160.ArticlePubMed

- 18. Waplington M, Lumley PJ, Walmsley AD, Blunt L. Cutting ability of an ultrasonic retrograde cavity preparation instrument. Endod Dent Traumatol 1995;11:177-180.ArticlePubMed

- 19. Aydemir S, Cimilli H, Mumcu G, Chandler N, Kartal N. Crack formation on resected root surfaces subjected to conventional, ultrasonic, and laser root-end cavity preparation. Photomed Laser Surg 2014;32:351-355.ArticlePubMed

- 20. Wallace JA. Effect of Waterlase laser retrograde root-end cavity preparation on the integrity of root apices of extracted teeth as demonstrated by light microscopy. Aust Endod J 2006;32:35-39.ArticlePubMed

- 21. Torabinejad M, Smith PW, Kettering JD, Pitt Ford TR. Comparative investigation of marginal adaptation of mineral trioxide aggregate and other commonly used root-end filling materials. J Endod 1995;21:295-299.ArticlePubMed

- 22. Xavier CB, Weismann R, de Oliveira MG, Demarco FF, Pozza DH. Root-end filling materials: apical microleakage and marginal adaptation. J Endod 2005;31:539-542.ArticlePubMed

- 23. Bidar M, Moradi S, Jafarzadeh H, Bidad S. Comparative SEM study of the marginal adaptation of white and grey MTA and Portland cement. Aust Endod J 2007;33:2-6.ArticlePubMed

- 24. Pécora JD, Cussioli AL, Guerişoli DM, Marchesan MA, Sousa-Neto MD, Brugnera Júnior A. Evaluation of Er:YAG laser and EDTAC on dentin adhesion of six endodontic sealers. Braz Dent J 2001;12:27-30.PubMed

- 25. Karlovic Z, Pezelj-Ribaric S, Miletic I, Jukic S, Grgurevic J, Anic I. Erbium:YAG laser versus ultrasonic in preparation of root-end cavities. J Endod 2005;31:821-823.ArticlePubMed

- 26. Soundappan S, Sundaramurthy JL, Raghu S, Natanasabapathy V. Biodentine versus mineral trioxide aggregate versus ıntermediate restorative material for retrograde root end filling: an ınvitro study. J Dent (Tehran) 2014;11:143-149.PubMedPMC

- 27. Ravi Chandra PV, Vemisetty H, Deepti K, Reddy SJ, Ramkiran D, Krishna MJN, et al. Comparative evaluation of marginal adaptation of biodentine(TM) and other commonly used root end filling materials-an ınvitro study. J Clin Diagn Res 2014;8:243-245.ArticlePMC

- 28. Khandelwal A, Karthik J, Nadig RR, Jain A. Sealing ability of mineral trioxide aggregate and Biodentine as root end filling material, using two different retro preparation techniques: an in vitro study. Int J Contemp Dent Med Rev 2015;2015:150115.

- 29. Han L, Okiji T. Uptake of calcium and silicon released from calcium silicate-based endodontic materials into root canal dentine. Int Endod J 2011;44:1081-1087.ArticlePubMed

- 30. Koch K, Brave D, Ali Nasseh A. A review of bioceramic technology in endodontics. Roots 2013;1:6-13.

- 31. Alanezi AZ, Jiang J, Safavi KE, Spangberg LS, Zhu Q. Cytotoxicity evaluation of endosequence root repair material. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 2010;109:e122-e125.ArticlePubMed

- 32. Shokouhinejad N, Nekoofar MH, Ashoftehyazdi K, Zahraee S, Khoshkhounejad M. Marginal adaptation of new bioceramic materials and mineral trioxide aggregate: a scanning electron microscopy study. Iran Endod J 2014;9:144-148.PubMedPMC

- 33. Lertmalapong P, Jantarat J, Srisatjaluk RL, Komoltri C. Bacterial leakage and marginal adaptation of various bioceramics as apical plug in open apex model. J Investig Clin Dent 2019;10:e12371.ArticlePubMedPDF

, Seda Aydemir2,*

, Seda Aydemir2,* , Nicholas Paul Chandler3

, Nicholas Paul Chandler3

KACD

KACD

ePub Link

ePub Link Cite

Cite