Articles

- Page Path

- HOME > Restor Dent Endod > Volume 47(3); 2022 > Article

- Research Article Association between cigarette smoking and the prevalence of post-endodontic periapical pathology: a systematic review and meta-analysis

-

Néstor Ríos-Osorio1

, Hernan Darío Muñoz-Alvear2

, Hernan Darío Muñoz-Alvear2 , Fabio Andrés Jiménez-Castellanos3

, Fabio Andrés Jiménez-Castellanos3 , Sara Quijano-Guauque1

, Sara Quijano-Guauque1 , Oscar Jiménez-Peña1

, Oscar Jiménez-Peña1 , Herney Andrés García-Perdomo4

, Herney Andrés García-Perdomo4 , Javier Caviedes-Bucheli5

, Javier Caviedes-Bucheli5

-

Restor Dent Endod 2022;47(3):e27.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.5395/rde.2022.47.e27

Published online: June 13, 2022

1Research Department COC-CICO, Institución Universitaria Colegios de Colombia UNICOC, Bogotá, Colombia.

2Department of Endodontics Universidad cooperativa de Colombia, Bogotá, Colombia.

3Department of Periodontics, Universidad Antonio Nariño, Bogotá, Colombia.

4Department of Surgery and Urology, School of Medicine Universidad del Valle, Cali, Colombia.

5Centro de Investigaciones Odontologicas, Pontificia Universidad Javeriana, Bogota, Colombia.

- Correspondence to Néstor Ríos-Osorio, DDS, MSc. Associate Professor, Research Department COC-CICO, Institución Universitaria Colegios de Colombia UNICOC, Km 20, Autonorte I-55, Chía, Cundinamarca, Bogotá, Colombia. dadopi1981@gmail.com

Copyright © 2022. The Korean Academy of Conservative Dentistry

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/) which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Abstract

-

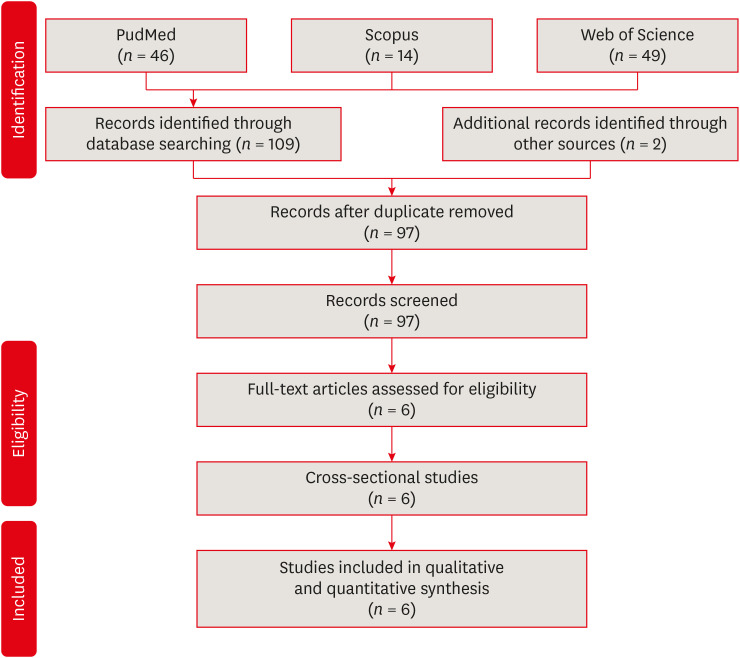

Objectives This systematic review and meta-analysis aimed to assess the association of cigarette smoking with the prevalence of post-endodontic apical periodontitis in humans.

-

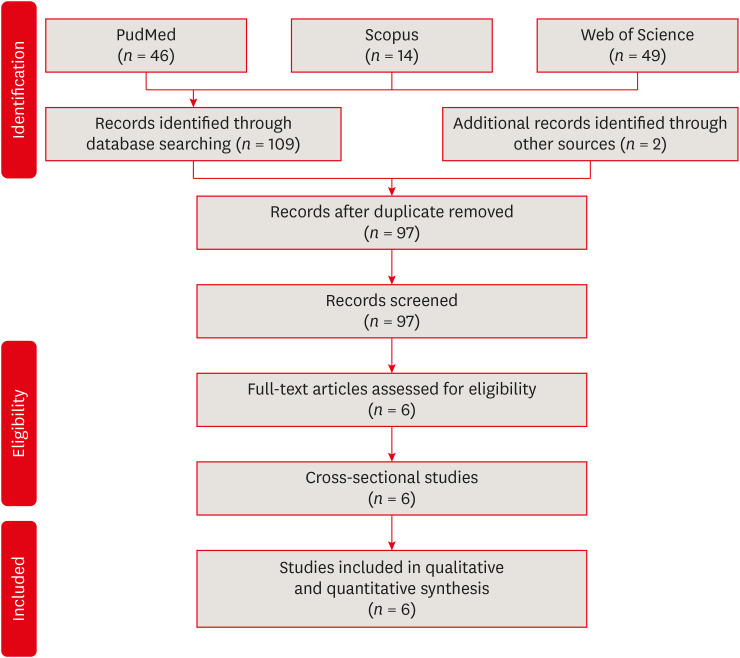

Materials and Methods We searched through PubMed/Medline, Web of Science, and Scopus from inception to December 2020. Risk of bias was performed by using the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale for cross-sectional, cohort, and case-control studies. We performed the statistical analysis in Review Manager 5.3 (RevMan 5.3).

-

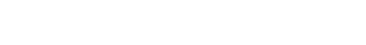

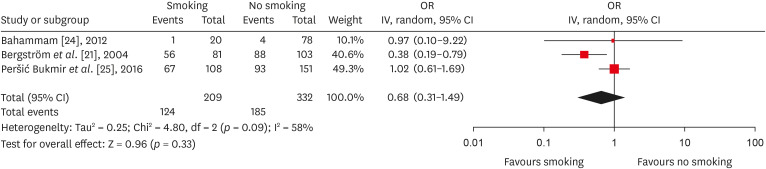

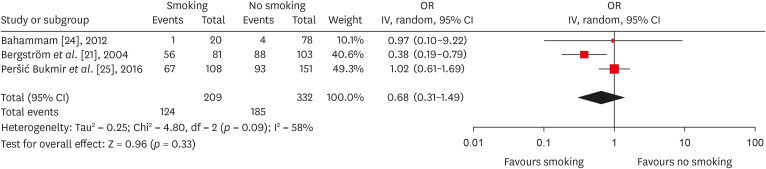

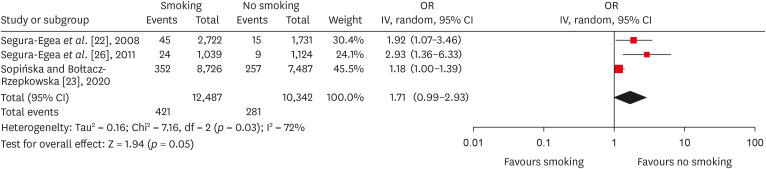

Results 6 studies met the inclusion criteria for qualitative and quantitative synthesis. Statistical analysis of these studies suggests that there were no differences in the prevalence of post endodontic apical periodontitis (AP) when comparing non-smokers vs smoker subjects regarding patients (odds ratio [OR], 0.68; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.31–1.49; I2 = 58%) and teeth (OR, 1.71; 95% CI, 0.99–2.93; I2 = 72%).

-

Conclusions Our findings suggest that there was no association between cigarette smoking and post-endodontic apical periodontitis, as we did not find statistical differences in the prevalence of post-endodontic AP when comparing non-smokers vs smoker subjects. Therefore, smoking should not be considered a risk factor associated with endodontic failure.

INTRODUCTION

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Population: CS patients.

Intervention: History of conventional root canal treatment (RCT).

Comparison: Non-CS patients.

Outcome: Prevalence of post-endodontic apical periodontitis.

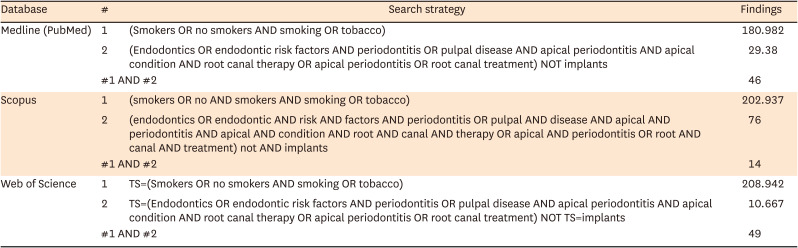

1. (Smokers OR no smokers AND smoking OR tobacco)

2. (Endodontics OR endodontic risk factors AND periodontitis OR pulpal disease AND apical periodontitis AND apical condition AND root canal therapy OR apical periodontitis OR root canal treatment) NOT implants

1. (smokers OR no AND smokers AND smoking OR tobacco)

2. (endodontics OR endodontic AND risk AND factors AND periodontitis OR pulpal AND disease AND apical AND periodontitis AND apical AND condition AND root AND canal AND therapy OR apical AND periodontitis OR root AND canal AND treatment) not AND implants

1. TS=(Smokers OR no smokers AND smoking OR tobacco)

2. TS=(Endodontics OR endodontic risk factors AND periodontitis OR pulpal disease AND apical periodontitis AND apical condition AND root canal therapy OR apical periodontitis

RESULTS

Characteristics of studies assessing the post endodontic prevalence of AP in smokers vs non-smokers patient

| Article | Author, year, country | Sample (n) | Age | Sample characteristics (smoker and/or non-smoker) | Teeth (n) (smoker and/or non-smoker) | Periapical diagnosis | PAI | Main results | Statistical analysis | Confidence level | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Bergström et al. [21], 2004, Sweden | Subjects n = 247, male (n = 213), female (n = 34) | 20–65 | Current smokers (n = 81), former smokers (n = 63), non-smokers (n = 103) | On average for the total sample: 38.7 out of a maximum of 42 dental roots per person (i.e. 92%) were available for assessment. | Periapical radiographs | No | The mean numbers of periapical lesions per person related to endodontically treated teeth for current smokers: n = 0.86 mean; 95% CI, 0.5–1.2. Former smokers: n = 0.53 mean; 95% CI, 0.3–0.8. Non-smokers: n = 0.68 mean; 95% CI, 0.4–0.9. Total: n = 0.30 mean; 95% CI, 0.5–0.8. The smoking prevalence of individuals exhibiting one or more teeth with a periapical lesion: current smokers (56%), former smokers (57%), and non-smokers (46%) (p > 0.05). The prevalence of periapical lesions among individuals with RCT: current smokers (69%), former-smokers (74%), and non-smokers (85%) (p > 0.05). | Kolmogorov–Smirnov test, Kruskal–Wallis non-parametric ANOVA, two-factor ANOVA, and Scheffé post hoc multiple comparisons test | p < 0.05 | It is concluded that these observations do not support the assumption that smoking is associated with apical periodontitis. Moreover, there was no statistically difference (p > 0.05) in terms of root-filled teeth with AP when comparing smokers vs non-smokers. |

| 2 | Segura-egea et al. [22], 2008, Spain | Subjects n = 180, male (n = 66, 36.7%), female (n = 114, 63.3%) | 37.1 ± 15.7 | Current smokers (n = 109, 61%) and non-smokers (n = 71, 39%) | Total number of teeth examined in smokers was 2,722 and 1,731 teeth in non-smokers. The average number of teeth per patient: smokers (n = 25.0 ± 3.8), non-smoker (n = 24.4 ± 4.5) (p > 0.05). | Periapical radiographs | Yes | AP in one or more teeth in smokers (n = 81, 74%) and non-smokers (n = 29, 41%) (p < 0.01; OR, 4.2; 95% CI, 2.2–7.9). Among smokers, 45 root-filled teeth had AP, whereas in non-smokers 15 (OR non-smokers = 1.0, OR smokers = 1.5, p > 0.05). | Cohen’s Kappa test, ANOVA and logistic regression | p < 0.05 | Smoking was significantly associated with a higher frequency and prevalence of root canal treatment and apical periodontitis. However, there was no statistically difference (p > 0.05) in terms of root-filled teeth with AP when comparing smokers vs non-smokers. |

| 3 | Sopińska and Bołtacz-Rzepkowska [23], 2020, Poland | Subjects n = 703, male (n = 277, 39.4%), female (n = 426, 60.6%) | 18–91 | Non-smokers (n = 317), smokers (n = 386) | Total number of teeth examined in smokers was 8,726 and 7,487 teeth in non-smokers. | Panoramic radiographs | No | Smokers presented a higher prevalence of teeth with AP than non-smokers (7.2% and 5.2% respectively, p < 0.0005). Among smokers, 352 root-filled teeth had AP, whereas in non-smokers 257 (χ2 test p = 0.451; Mantel-Haenszel test 0.760; common OR estimate 0.963; 95% CI, 0.783–1.184). | χ2 and the Mantel-Haenszel test | p > 0.05 | Smokers are a group facing an increased risk of AP. However, no difference was observed in the frequency of AP in the endodontically treated teeth in both groups (37.6% vs 35.8%) (p = 0.451). |

| 4 | Bahammam [24], 2012, Saudi Arabia | Subjects n = 98 male individuals | 20–60 | Non-smokers (n = 78), smokers (n = 20) | The average number of teeth per patient was 24.65 ± 3.28 and 24.58 ± 4.41 in smokers and non-smokes, respectively (p = 0.953). | Periapical radiographs | No | The prevalence of patients with AP was 8.59% in smoker and 6.18% in non-smokers. The frequency of patients having AP with RCT in smoker and in non-smokers was 5.73% and 5.12%, respectively (p = 0.195). | t-test | p < 0.05 | Results from this study do not favor the assumption that smoking is associated with AP. Likewise, there was no statistically difference (p > 0.05) in terms of root-filled teeth with AP when comparing smokers vs non-smokers. |

| 5 | Peršić Bukmir et al. [25], 2015, Croatia | Subjects n = 259, 82 male subjects (31.7%) and 177 female subjects (68.3%). | 40.3 ± 15.1 | Non-smokers (n = 151), smokers (n = 108) | The average number of teeth per patient was 22.9 ± 5.2 and 23.2 ± 4.9 in smokers and non-smokes, respectively (p = 0.636). | Panoramic radiographs and Periapical radiographs | Yes | Smokers had higher prevalence of teeth with AP than non-smokers (0.13 vs 0.10; p = 0.025). Among smokers, 67 patients (72.0%) had AP affecting at least one treated tooth, whereas in non-smokers, 93 patients (78.8%) had AP affecting at least one treated tooth (p = 0.328). Likewise, fractions of endodontically treated teeth with AP did not differ significantly between smokers vs non-smokers (mean, 0.06; SD, 0.07; 95% CI, 0.05–0.07; p = 0.832). | Kolmogorov–Smirnov test, t-test and χ2 test | p < 0.05 | Smokers will on average have two teeth with AP more than non-smokers, thus supporting the hypothesis that smoking influences the periapical status of teeth. However, no difference was observed in the prevalence of AP in the endodontically treated teeth when comparing smokers vs non-smokers (72.0% and 78.8% respectively) (p = 0.328). |

| 6 | Segura-egea et al. [26], 2011, Spain | Subjects n = 100, men (n = 53, 53%) women (n = 47, 47%) | 58.7 ± 9.6 | 50 smokers and 50 non-smokers | Total number of teeth examined in smokers was 1,039 and 1,124 teeth in non-smokers. The average number of teeth per patient: smokers (n = 20.8 ± 4.0), non-smokers (n = 22.3 ± 4.3) (p > 0.05). | Periapical radiographs | Yes | AP in one or more teeth in smokers (n = 46, 92%) and non-smokers (n = 22, 44%) (p < 0.01; OR, 14.6; 95% CI: 4.6–46.9). Among smokers, 24 root-filled teeth had AP whereas in non-smokers, 9 root-filled teeth exhibited AP (p > 0.05). | Student t-test, logistic regression and χ2 test | p < 0.05 | The prevalence of apical periodontitis and root canal treatment was significantly higher in hypertensive smoking patients compared to non-smokers. However, there was no statistically difference (p > 0.05) in terms of root-filled teeth with AP when comparing smokers vs non-smokers. |

Evaluation according to the Newcastle-Ottawa quality assessment scale

| Study | Selection | Comparability | Outcome | Conclusion | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cross-sectional studies | |||||

| Bergström et al. [21], 2004 | - | ★★ | ★★★ | HIGH RISK | |

| Segura-Egea et al. [22], 2008 | - | ★★ | ★★★ | HIGH RISK | |

| Sopińska and Bołtacz-Rzepkowska [23], 2020 | ★★ | ★★ | ★★★ | LOW RISK | |

| Bahammam [24], 2012 | ★ | - | ★★★ | HIGH RISK | |

| Peršić Bukmir et al. [25], 2016 | ★★ | ★★ | ★★★ | LOW RISK | |

| Segura-Egea et al. [26], 2011 | - | ★★ | ★★★ | HIGH RISK | |

Forest plot of association between root canal treatment with apical periodontitis in smokers vs non-smokers subjects (analysis by patients).

Forest plot of association between root canal treatment with apical periodontitis in smokers vs non-smokers subjects (analysis by teeth).

DISCUSSION

CONCLUSIONS

-

Conflict of Interest: No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

-

Author Contributions:

Conceptualization: Ríos-Osorio N.

Data curation: Jiménez-Peña O, Muñoz-Alvear HD.

Formal analysis: García-Perdomo HA.

Investigation: Quijano S, Caviedes-Bucheli J.

Methodology: Muñoz-Alvear HD, Jiménez- Peña O, Caviedes-Bucheli J.

Project administration: Ríos-Osorio N.

Software: Muñoz-Alvear HD.

Supervision: Jiménez-Castellanos FA.

Validation: Quijano S, Caviedes-Bucheli J.

Visualization: Quijano S.

Writing - original draft: Ríos-Osorio N.

Writing - review & editing: Ríos-Osorio N, Jiménez-Castellanos FA, García-Perdomo HA.

- 1. Calafat AM, Polzin GM, Saylor J, Richter P, Ashley DL, Watson CH. Determination of tar, nicotine, and carbon monoxide yields in the mainstream smoke of selected international cigarettes. Tob Control 2004;13:45-51.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 2. Manuela R, Mario M, Vincenzo R, Filippo R. Nicotine stimulation increases proliferation and matrix metalloproteinases-2 and -28 expression in human dental pulp cells. Life Sci 2015;135:49-54.ArticlePubMed

- 3. Kissela BM, Khoury J, Kleindorfer D, Woo D, Schneider A, Alwell K, Miller R, Ewing I, Moomaw CJ, Szaflarski JP, Gebel J, Shukla R, Broderick JP. Epidemiology of ischemic stroke in patients with diabetes: the greater Cincinnati/Northern Kentucky Stroke Study. Diabetes Care 2005;28:355-359.PubMed

- 4. Esfahrood ZR, Zamanian A, Torshabi M, Abrishami M. The effect of nicotine and cotinine on human gingival fibroblasts attachment to root surfaces. J Basic Clin Physiol Pharmacol 2015;26:517-522.ArticlePubMed

- 5. Kinnula VL. Focus on antioxidant enzymes and antioxidant strategies in smoking related airway diseases. Thorax 2005;60:693-700.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 6. Reibel J. Tobacco and oral diseases. Update on the evidence, with recommendations. Med Princ Pract 2003;12(Suppl 1):22-32.ArticlePubMedPDF

- 7. Cano M, Thimmalappula R, Fujihara M, Nagai N, Sporn M, Wang AL, Neufeld AH, Biswal S, Handa JT. Cigarette smoking, oxidative stress, the anti-oxidant response through Nrf2 signaling, and Age-related Macular Degeneration. Vision Res 2010;50:652-664.ArticlePubMed

- 8. Özsezer Demiryürek E, Sakallıoğlu EE, Kalyoncuoğlu E, Yılmaz Miroğlu Y, Sakallıoğlu U. The effects of smoking on the osmotic pressure of human dental pulp tissue. Med Princ Pract 2015;24:465-469.ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 9. Scott DA, Poston RN, Wilson RF, Coward PY, Palmer RM. The influence of vitamin C on systemic markers of endothelial and inflammatory cell activation in smokers and non-smokers. Inflamm Res 2005;54:138-144.ArticlePubMedPDF

- 10. Krall EA, Abreu Sosa C, Garcia C, Nunn ME, Caplan DJ, Garcia RI. Cigarette smoking increases the risk of root canal treatment. J Dent Res 2006;85:313-317.ArticlePubMedPDF

- 11. Caviedes-Bucheli J, Gomez-Sosa JF, Azuero-Holguin MM, Ormeño-Gomez M, Pinto-Pascual V, Munoz HR. Angiogenic mechanisms of human dental pulp and their relationship with substance P expression in response to occlusal trauma. Int Endod J 2017;50:339-351.ArticlePubMedPDF

- 12. Ríos-Osorio N, Muñoz-Alvear HD, Montoya Cañón S, Restrepo-Mendez S, Aguilera-Rojas SE, Jiménez-Peña O, García-Perdomo HA. Association between type 2 diabetes mellitus and the evolution of endodontic pathology. Quintessence Int 2020;51:100-107.PubMed

- 13. Fröhlich M, Sund M, Löwel H, Imhof A, Hoffmeister A, Koenig W. Independent association of various smoking characteristics with markers of systemic inflammation in men. Results from a representative sample of the general population (MONICA Augsburg Survey 1994/95). Eur Heart J 2003;24:1365-1372.ArticlePubMed

- 14. Ijzerman RG, Serne EH, van Weissenbruch MM, de Jongh RT, Stehouwer CD. Cigarette smoking is associated with an acute impairment of microvascular function in humans. Clin Sci (Lond) 2003;104:247-252.ArticlePubMedPDF

- 15. Barbieri SS, Zacchi E, Amadio P, Gianellini S, Mussoni L, Weksler BB, Tremoli E. Cytokines present in smokers’ serum interact with smoke components to enhance endothelial dysfunction. Cardiovasc Res 2011;90:475-483.ArticlePubMed

- 16. Johannsen A, Susin C, Gustafsson A. Smoking and inflammation: evidence for a synergistic role in chronic disease. Periodontol 2000 2014;64:111-126.ArticlePubMed

- 17. Pinto KP, Ferreira CM, Maia LC, Sassone LM, Fidalgo TK, Silva EJ. Does tobacco smoking predispose to apical periodontitis and endodontic treatment need? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int Endod J 2020;53:1068-1083.ArticlePubMedPDF

- 18. Aminoshariae A, Kulild J, Gutmann J. The association between smoking and periapical periodontitis: a systematic review. Clin Oral Investig 2020;24:533-545.ArticlePubMedPDF

- 19. Urrútia G, Bonfill X. PRISMA declaration: a proposal to improve the publication of systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Med Clin (Barc) 2010;135:507-511.PubMed

- 20. Wells GA, Shea B, O’Connell D, Peterson J, Welch V, Losos M, Tugwell P. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses [Internet]. Ottawa, ON: Ottawa Hospital Research Institute; 2019. cited 2020 Nov 4]. Available from: http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp.

- 21. Bergström J, Babcan J, Eliasson S. Tobacco smoking and dental periapical condition. Eur J Oral Sci 2004;112:115-120.ArticlePubMed

- 22. Segura-Egea JJ, Jiménez-Pinzón A, Ríos-Santos JV, Velasco-Ortega E, Cisneros-Cabello R, Poyato-Ferrera MM. High prevalence of apical periodontitis amongst smokers in a sample of Spanish adults. Int Endod J 2008;41:310-316.ArticlePubMed

- 23. Sopińska K, Bołtacz-Rzepkowska E. The influence of tobacco smoking on dental periapical condition in a sample of an adult population of the Łódź region, Poland. Int J Occup Med Environ Health 2020;33:45-57.ArticlePubMed

- 24. Bahammam LA. Tobacco smoking and dental periapical condition in a sample of Saudi Arabian sub-population. J King Abdulaziz Univ Med Sci 2012;19:35-41.Article

- 25. Peršić Bukmir R, Jurčević Grgić M, Brumini G, Spalj S, Pezelj-Ribaric S, Brekalo Pršo I. Influence of tobacco smoking on dental periapical condition in a sample of Croatian adults. Wien Klin Wochenschr 2016;128:260-265.ArticlePubMedPDF

- 26. Segura-Egea JJ, Castellanos-Cosano L, Velasco-Ortega E, Ríos-Santos JV, Llamas-Carreras JM, Machuca G, López-Frías FJ. Relationship between smoking and endodontic variables in hypertensive patients. J Endod 2011;37:764-767.ArticlePubMed

- 27. Metzger Z, Abramovitz I. Periapical lesions of endodontic origin. In: Ingle JI, Bakland LK, Baumgartner JC, editors. Ingle’s endodontics. 6th ed. Hamilton, ON: BC Decker; 2009. p. 494-519.

- 28. Kettering JD, Torabinejad M, Jones SL. Specificity of antibodies present in human periapical lesions. J Endod 1991;17:213-216.ArticlePubMed

- 29. Baumgartner JC, Falkler WA Jr. Biosynthesis of IgG in periapical lesion explant cultures. J Endod 1991;17:143-146.ArticlePubMed

- 30. Lieberman JR, Daluiski A, Einhorn TA. The role of growth factors in the repair of bone. Biology and clinical applications. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2002;84:1032-1044.PubMed

- 31. Hofbauer LC, Heufelder AE. Role of receptor activator of nuclear factor-kappaB ligand and osteoprotegerin in bone cell biology. J Mol Med (Berl) 2001;79:243-253.PubMed

- 32. Hofbauer LC, Kühne CA, Viereck V. The OPG/RANKL/RANK system in metabolic bone diseases. J Musculoskelet Neuronal Interact 2004;4:268-275.PubMed

- 33. Holland R, Gomes JE, Cintra LTA, Queiroz ÍOA, Estrela C. Factors affecting the periapical healing process of endodontically treated teeth. J Appl Oral Sci 2017;25:465-476.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 34. Maeda H, Wada N, Nakamuta H, Akamine A. Human periapical granulation tissue contains osteogenic cells. Cell Tissue Res 2004;315:203-208.ArticlePubMedPDF

- 35. Ørstavik D. Time-course and risk analyses of the development and healing of chronic apical periodontitis in man. Int Endod J 1996;29:150-155.ArticlePubMed

- 36. Ng YL, Mann V, Rahbaran S, Lewsey J, Gulabivala K. Outcome of primary root canal treatment: systematic review of the literature - part 1. Effects of study characteristics on probability of success. Int Endod J 2007;40:921-939.ArticlePubMed

- 37. Siqueira JF Jr, Rôças IN, Riche FN, Provenzano JC. Clinical outcome of the endodontic treatment of teeth with apical periodontitis using an antimicrobial protocol. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 2008;106:757-762.ArticlePubMed

- 38. Azim AA, Griggs JA, Huang GT. The Tennessee study: factors affecting treatment outcome and healing time following nonsurgical root canal treatment. Int Endod J 2016;49:6-16.ArticlePubMed

- 39. Duncan HF, Pitt Ford TR. The potential association between smoking and endodontic disease. Int Endod J 2006;39:843-854.ArticlePubMed

- 40. Segura-Egea JJ, Martín-González J, Castellanos-Cosano L. Endodontic medicine: connections between apical periodontitis and systemic diseases. Int Endod J 2015;48:933-951.ArticlePubMed

- 41. Lehr HA. Microcirculatory dysfunction induced by cigarette smoking. Microcirculation 2000;7:367-384.ArticlePubMed

- 42. Wong LS, Green HM, Feugate JE, Yadav M, Nothnagel EA, Martins-Green M. Effects of “second-hand” smoke on structure and function of fibroblasts, cells that are critical for tissue repair and remodeling. BMC Cell Biol 2004;5:13.ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 43. Marending M, Peters OA, Zehnder M. Factors affecting the outcome of orthograde root canal therapy in a general dentistry hospital practice. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 2005;99:119-124.ArticlePubMed

- 44. Touré B, Faye B, Kane AW, Lo CM, Niang B, Boucher Y. Analysis of reasons for extraction of endodontically treated teeth: a prospective study. J Endod 2011;37:1512-1515.ArticlePubMed

- 45. Danin J, Linder LE, Lundqvist G, Andersson L. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha and transforming growth factor-beta1 in chronic periapical lesions. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 2000;90:514-517.ArticlePubMed

- 46. Wu MK, Shemesh H, Wesselink PR. Limitations of previously published systematic reviews evaluating the outcome of endodontic treatment. Int Endod J 2009;42:656-666.ArticlePubMed

- 47. Patel S, Dawood A, Whaites E, Pitt Ford T. New dimensions in endodontic imaging: part 1. Conventional and alternative radiographic systems. Int Endod J 2009;42:447-462.ArticlePubMed

REFERENCES

Appendix

Tables & Figures

REFERENCES

Citations

- The role of smoking as a risk indicator for apical periodontitis and endodontic status: a cross-sectional study of a portuguese adult sample

Isabel Silva Martins, Natália Pestana de Vasconcelos, Américo Santos Afonso, Ana Cristina Braga, Irene Pina-Vaz

Odontology.2026;[Epub] CrossRef - RISK FACTORS FOR CHRONIC APICAL PERIODONTITIS ACCORDING TO THE CASE-CONTROL STUDY

N. Bagryantseva

Vrach.2026; : 43. CrossRef

Figure 1

Figure 2

Figure 3

Characteristics of studies assessing the post endodontic prevalence of AP in smokers vs non-smokers patient

| Article | Author, year, country | Sample ( | Age | Sample characteristics (smoker and/or non-smoker) | Teeth ( | Periapical diagnosis | PAI | Main results | Statistical analysis | Confidence level | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Bergström | Subjects | 20–65 | Current smokers ( | On average for the total sample: 38.7 out of a maximum of 42 dental roots per person (i.e. 92%) were available for assessment. | Periapical radiographs | No | The mean numbers of periapical lesions per person related to endodontically treated teeth for current smokers: | Kolmogorov–Smirnov test, Kruskal–Wallis non-parametric ANOVA, two-factor ANOVA, and Scheffé | It is concluded that these observations do not support the assumption that smoking is associated with apical periodontitis. Moreover, there was no statistically difference ( | |

| 2 | Segura-egea | Subjects | 37.1 ± 15.7 | Current smokers ( | Total number of teeth examined in smokers was 2,722 and 1,731 teeth in non-smokers. The average number of teeth per patient: smokers ( | Periapical radiographs | Yes | AP in one or more teeth in smokers ( | Cohen’s Kappa test, ANOVA and logistic regression | Smoking was significantly associated with a higher frequency and prevalence of root canal treatment and apical periodontitis. However, there was no statistically difference ( | |

| 3 | Sopińska and Bołtacz-Rzepkowska [ | Subjects | 18–91 | Non-smokers ( | Total number of teeth examined in smokers was 8,726 and 7,487 teeth in non-smokers. | Panoramic radiographs | No | Smokers presented a higher prevalence of teeth with AP than non-smokers (7.2% and 5.2% respectively, | χ2 and the Mantel-Haenszel test | Smokers are a group facing an increased risk of AP. However, no difference was observed in the frequency of AP in the endodontically treated teeth in both groups (37.6% | |

| 4 | Bahammam [ | Subjects | 20–60 | Non-smokers ( | The average number of teeth per patient was 24.65 ± 3.28 and 24.58 ± 4.41 in smokers and non-smokes, respectively ( | Periapical radiographs | No | The prevalence of patients with AP was 8.59% in smoker and 6.18% in non-smokers. The frequency of patients having AP with RCT in smoker and in non-smokers was 5.73% and 5.12%, respectively ( | Results from this study do not favor the assumption that smoking is associated with AP. Likewise, there was no statistically difference ( | ||

| 5 | Peršić Bukmir | Subjects | 40.3 ± 15.1 | Non-smokers ( | The average number of teeth per patient was 22.9 ± 5.2 and 23.2 ± 4.9 in smokers and non-smokes, respectively ( | Panoramic radiographs and Periapical radiographs | Yes | Smokers had higher prevalence of teeth with AP than non-smokers (0.13 | Kolmogorov–Smirnov test, | Smokers will on average have two teeth with AP more than non-smokers, thus supporting the hypothesis that smoking influences the periapical status of teeth. However, no difference was observed in the prevalence of AP in the endodontically treated teeth when comparing smokers | |

| 6 | Segura-egea | Subjects | 58.7 ± 9.6 | 50 smokers and 50 non-smokers | Total number of teeth examined in smokers was 1,039 and 1,124 teeth in non-smokers. The average number of teeth per patient: smokers ( | Periapical radiographs | Yes | AP in one or more teeth in smokers ( | Student | The prevalence of apical periodontitis and root canal treatment was significantly higher in hypertensive smoking patients compared to non-smokers. However, there was no statistically difference ( |

AP, apical periodontitis; PAI, periapical index; CI, Confidence interval; RCT, root canal treatment; ANOVA, analysis of variance; OR, odds ratio; SD, standard deviation.

Evaluation according to the Newcastle-Ottawa quality assessment scale

| Study | Selection | Comparability | Outcome | Conclusion | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Bergström | - | ★★ | ★★★ | HIGH RISK | |

| Segura-Egea | - | ★★ | ★★★ | HIGH RISK | |

| Sopińska and Bołtacz-Rzepkowska [ | ★★ | ★★ | ★★★ | LOW RISK | |

| Bahammam [ | ★ | - | ★★★ | HIGH RISK | |

| Peršić Bukmir | ★★ | ★★ | ★★★ | LOW RISK | |

| Segura-Egea | - | ★★ | ★★★ | HIGH RISK | |

AP, apical periodontitis; PAI, periapical index; CI, Confidence interval; RCT, root canal treatment; ANOVA, analysis of variance; OR, odds ratio; SD, standard deviation.

KACD

KACD

ePub Link

ePub Link Cite

Cite